Tech Things: Why did NVIDIA buy Groq?

Understanding Groq's unique value add and NVIDIA's decision calculus.

This one happened while I was traveling on my honeymoon, so I almost missed it. Apologies for being a bit behind.

Sometimes when I get philosophical, I ask myself “What exactly is a company?” There’s a legal definition — a company is a piece of paper in Delaware. But that’s really only useful if you’re being pedantic or you’re a lawyer (but I repeat myself). A company has a lot of constituent parts. There’s employees and there’s IP and there’s cash and there’s customer relationships. But if you just bundled a random assortment of these things together, is it a company?

As a serial founder I feel like there’s some missing glue, something that animates the company, that gives it life. People are composed of cells and organs and electrical signals. But there’s this magic other thing, a soul, that seems necessary to make the whole apparatus function as a person. I think the same is true of a company. Companies have their mechanical pieces, but they also have a soul, and the soul of a company is diffuse and lives in the gaps.

A few months ago, we discussed Meta’s pseudo acquisition of Scale AI.

It was sorta weird. There wasn’t any official M&A process, and legally Scale AI still exists as a separate entity. But also, most of Scale’s talent has departed for Meta, leaving behind…what, exactly? There is still IP, and there are still employees, and there is a lot of cash floating around. But the general consensus is that the company was “acquired”. How can Scale be acquired if Scale AI still exists? If you ask me, Meta acquired the soul of Scale AI, and left behind the legal corpse. Since the “acquisition”, Scale has been limping along, a zombie. From Business Insider:

…

The vast army of human data labelers that made Scale AI a juggernaut are chafing at what they say are pay cuts, lengthy unpaid onboarding sessions to join new AI projects, and thinning workloads — and are increasingly leaving the platform altogether, according to interviews with five current and former contractors and internal correspondence obtained by Business Insider.…

Just a few weeks after the investment, he was laid off as part of a major downsizing that saw 14% of Scale AI’s full-time staff of 1,400 let go…Those weren’t the only cuts. In September, Scale AI terminated 12 contractors on its red team, citing performance issues. Two ex-red teamers told Business Insider that the team’s work had been drying up since the Meta deal, blaming thinning workloads for the cuts. Later that month, Scale AI shuttered a team in Dallas of contractors focused on generalist AI work as it moved towards more specialized fields.

…

Other investors see Scale AI as more like a gutted fish. The Meta investment — which valued Scale AI at $29 billion — has dented Scale AI’s valuation in private markets where people buy and sell equity from pre-IPO startups. Noel Moldvai, Augment’s CEO, tells Business Insider his platform used to process millions of dollars’ worth of transactions in Scale AI stock before the Meta deal, but that dried up as sellers waited to see if the startup rebounded...The underlying message of Meta’s semi-acquisition is clear to Moldvai. “It seems like Meta was just after Alexandr Wang, and so this is probably the structure that let them get him,” he says.

…

If the company doesn't pull it off, it could become the latest example of a once-promising startup that morphed into a "zombie" after being invested in by a tech giant.

Meta’s acquisition of Scale follows a few other similar exits. I previously wrote about how windsurf was “acquired” by Google, for example, which resulted in the Cognition team picking up the scraps. Google also “acquired” Character AI, a company that, last I checked, is facing a half dozen lawsuits and is getting take-down notices left and right against its core business.

As a legal fiction, these aren’t technically acquisitions. But empirically, it’s not a great track record for the company that’s been left behind, is it? I’m not the first person to notice the spiritual parallels. Kevin Kwok wrote about this back in July:

I propose we call them HALO deals.

“Halo” comes from “Hire and license out.”

Besides being a backronym it meets the two other requirements for naming a transaction type: Sounding benign and being descriptive. People with halos have left their bodies to live somewhere in the cloud giants.

Well said.

Anyway, the big news over the holidays was that NVIDIA was getting in on the action by “acquiring” (halo-ing?) Groq. From Axios:

Groq and Nvidia on Wednesday announced a “non-exclusive licensing agreement,” with media reports accurately pegging the deal value at around $20 billion…

Most Groq shareholders will receive per-share distributions tied to the $20 billion valuation, according to sources…Around 90% of Groq employees are said to be joining Nvidia, and they will be paid cash for all vested shares. Their unvested shares will be paid out at the $20 billion valuation, but via Nvidia stock that vests on a schedule…

Groq had raised around $3.3 billion in venture capital funding since its 2016 founding, including a $750 million infusion this past fall at nearly a $7 billion post-money valuation.

NVIDIA is buying grok for nearly 3x its last valuation. That’s not the biggest markup I’ve ever heard, but given the last funding round was only three months prior, it definitely raises some eyebrows.

Groq1 is a company founded in 2016 by many of the senior engineers who built the TPU over at Google. I’ve written about TPUs a few times before.

For those who somehow are unaware, a TPU is a custom chip that is optimized for AI use cases. Google started investing in these back in 2013, way before the modern AI wars. They have been used internally to power most of Google’s training and inference, including for services like Search and Translate. TPUs are much more constrained than GPUs. GPUs can do lots of things. They can do all kinds of computation, and also sometimes they may even render a screen or display some graphics or something. By contrast, TPUs can only really do one thing — 8x128 matmuls. But they do that one thing very very efficiently.

Bluntly, TPUs just work. At the chip level, they are more stable and can be run at higher clock speeds for longer periods of time. At the server rack level, each TPU is wired so that they can efficiently communicate with all of the other TPUs in the rack with minimal latency. And at the datacenter level, you can wire together over 9000 TPUs acting in unison as a single pod. By comparison, with GPUs, you max out at less than 100. All of this together means that training bigger and more compute intensive models is easier and faster and likely cheaper on TPU stacks than on GPU stacks. Maybe even exponentially so.

I’ve been harping on the value of the TPU stack for a while now; the rest of the world seems to have finally taken notice. Anthropic was the first. Anthropic’s compute acquisition model has them sitting on top of the chip providers of the world. They have investment from both Amazon and Google in the form of cloud credits. My understanding is that the original versions of Claude were all trained on AWS GPUs. But for Claude Opus 4.5, they switched the GCP TPUs. Opus is currently Anthropic’s biggest model, it’s state of the art in programming, and it’s the model that I use basically all day every day.

Groq is kinda a big deal for the same reasons TPUs are kinda a big deal. GPUs are general purpose chips that can do everything from graphics processing to crypto mining. That generality is powerful, but it comes at the cost of being slower than hyper specialized ASICs.2 As tensor processing becomes more valuable, it makes more and more sense to leverage specialized chips that just do really fast matrix multiplications, and are designed from the ground up exclusively for matrix multiplications.

Groq is the fastest game in town for large language model inference.3 If you want near real-time text processing, eg for conversational voice agents or on-the-fly UI/UX processing or robotics, you go to grok.

The magic is in the chip design.

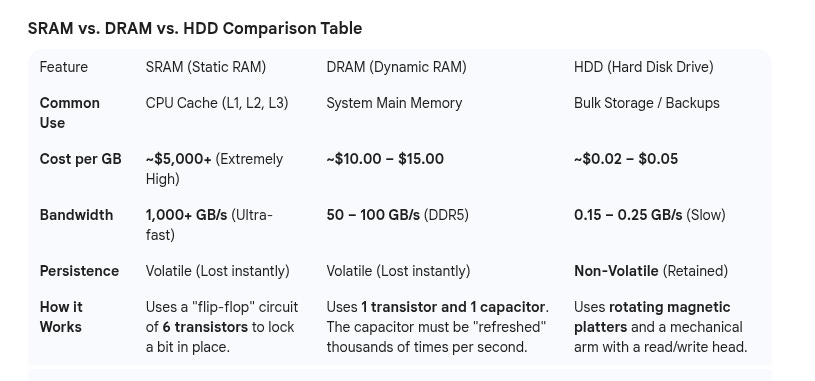

A brief tangent on computer memory. If you’ve ever built a computer, you may know that there is something called a hard drive and something called RAM (technically, DRAM). And you probably know that hard drive space is pretty cheap per gigabyte and good for long term storage of big chunky files, while RAM is more expensive per gigabyte and good for making your computer feel fast and zippy.4

The point of all computer data storage is to store ones and zeros over time. If I set something to a 1, it needs to stay as a 1 when I go retrieve it later. Traditional hard drives use a physical medium — magnetic tape — to store data. A little spinning wheel goes into a specific part of the tape and sets the magnetic polarity on the tape to a one or zero. Once set, the tape will retain its magnetic polarity for years and years. But that spinning wheel is an actual mechanical part, and as a result is really slow.

DRAM, by contrast, stores the data in a capacitor. Capacitors are little circuit components that store charge for short periods of time. A capacitor is ‘on’ when a certain amount of electric charge is filled up, and off when the charge is below the threshold. In order to hold state, it needs to constantly ‘refresh’ the capacitor charge, doing so thousands of times a second. DRAM is really fast because the data is all stored with electric charge, but without constant external power, it will slowly lose any stored data as the charge leaks out. If you’ve ever been asked to unplug your computer and then hit the power button, DRAM capacitors are why — trying to turn on the power when there’s no additional power source is a fast way to quickly drain all the capacitor charge, effectively resetting your RAM (and any corrupted memory that may be in there).5

Writing to disk is a bit like engraving a wax tablet. Writing to DRAM is a bit like writing your name on a foggy window. You trade off permanence for speed.6

Ok ok, now to throw a wrench in the whole thing. There is actually a secret third kind of memory, called SRAM. You basically never hear about SRAM in consumer settings because its price tag is enormous — $200 to $5000 per gigabyte. But they are wicked fast. The core unit of SRAM is a set of transistors. The transistor state stores the data value, and electricity is used to maintain the value. No need to wait until a capacitor is at full charge, no need to continually top off / refresh the capacitor state.7 You can just read the SRAM directly. People generally use SRAM for things like CPU registries — small bits of state that the CPU can read and write from really really quickly, so that it doesn’t spend most of its time waiting for DRAM memory lookups. Writing to SRAM is like setting a light switch. It’s near instant.

People dream of creating a computer that runs entirely on SRAM. It would be so fast. But it’s basically impossible to make the price work for a single consumer. Maybe you could amortize the cost across a bunch of users, but unfortunately there’s just no demand for super low latency data processing in a data center-like setting.

Back to groq. TPUs and CPUs use DRAM as external memory to the chip. You have to shuttle data from the memory to the main processing unit in order to do your matrix multiplications. The folks at grok said “fuck that” and decided to burn VC cash making a chip that is basically entirely SRAM. They call it the LPU, it costs $20000 for 230mb, and it can get to 500 tokens per second on Llama 70b. By comparison, an NVIDIA H100 ranges from 60-100 tokens per second. That quantitative difference puts groq in its own qualitative category. There are things you can do with groq — like robotics — that you just can’t do on NVIDIA chips.

The tradeoff is that you only have 230mb per chip. You can’t fit any real models on a chip that size, so you need to network a bunch of them together, and you need to be really clever about the networking to avoid that becoming the bottleneck. Running Llama 70b requires over 500 LPUs, which means a price tag of millions of dollars. And the best models are way bigger than 70b parameters.

I mention all of this because even though there are real use cases for groq’s tech, the market consensus so far has been ‘too expensive, too early’. All of the current killer apps for generative AI (code writing, chat bots) just don’t require ridiculously low latency. This is reflected in groq’s revenue and loss numbers. Groq did $90m in revenue in 2024 and burned $180m in capital — a $90m loss. And their initial revenue target of $2b in 2025 was revised down to below $500m, and now that 2025 is over and done it seems like they did under $200m in revenue.8 Nine years and several billion dollars of funding in, and this is still not exactly a sustainable business.

Which makes NVIDIA’s purchase all the more interesting.

It’s obvious why they wanted to do a HALO deal instead of an actual M&A — way less regulatory scrutiny, much faster turn-around time. But it’s less obvious why NVIDIA felt groq was worth acquiring, and as a result a lot of market analysts have spun their wheels trying to see what Jensen Huang sees. A few reasons I’ve heard floating around in the ether:

They wanted to smother a competitor in the crib, before it became a problem later.

They project a lot of growth in low latency use cases and want to build their own version of an LPU, and it was faster to just license the tech and the people.

They’re concerned about someone else buying groq (likely Google) and want to take that option off the table.

A few more conspiratorial minded folks think that there may be a political angle too — groq’s investors include folks who are connected to the Trump regime, and NVIDIA may have done this deal as a favor to try and loosen export restrictions on China. Unfortunately such quid pro quo deals are thoroughly unsurprising with this administration.

Honestly, if you ask me, I don’t think this deal is all that hard to understand, and I think it makes a ton of sense for NVIDIA. People forget just how much money NVIDIA has sloshing around right now. Before the groq purchase, NVIDIA had $60b lying around in cash reserves. This deal represented only 0.4% of its total market cap. Random market swings can eliminate or add many multiples of this acquisition price. If you could pick up an exciting new competitor for a fraction of your cash reserves, why wouldn’t you? It’s probably cheaper than spinning up your own R&D arm, and it gives NVIDIA an answer to the TPU.

I’m reminded a bit of when Zuckerberg purchased Insta for a billion dollars and everyone freaked out. Everyone, and I mean everyone, was convinced that a billion dollars was way too high a price for the fledgling social media platform. But the move was prescient, and now people wonder if that initial price was too low. I’m not saying that NVIDIA buying Groq is the same as Facebook buying Instagram, I just don’t know enough about semiconductors to make that claim with any certainty. But in many ways, NVIDIA has less exposure to risk than Facebook did back then, just because it is so much bigger. If robotics really takes off and NVIDIA can find a way to bring the Groq price-per-unit down, maybe this will seem as obvious in hindsight.

No relation to XAI’s “Grok”, which, after the latest incident, I just cannot bring myself to write about.

Application specific integrated circuits.

Besides maybe Cerebras, but that’s a post for a different time.

A consumer terabyte mechanical hard disk is about $50, so ~5 cents per gigabyte. 64 GB of DRAM is roughly $640, so $10 per gigabyte. A 200x price difference.

One really neat way to steal data from a computer is by physically stealing the RAM and then drenching it with liquid nitrogen. This slows the capacitor decay long enough to actually get useful information off the RAM.

SSDs are this weird hybrid thing that uses flash disk for hard drive storage. They work using something called Fowler Nordheim tunneling, AKA quantum magic. It’s easier to just imagine little elves that store the data for you.

When a DRAM chip is refreshing, it can’t do anything else. If the CPU asks for data during those few microseconds of refreshing, it has to wait. This adds lag and idle time to the CPU process.

We don’t have the burn amounts, unfortunately, but most reporting suggests they are still operating at a loss.

Wow, the part about a company's 'soul' is increadibly insightful, providing a vital framework for understanding modern tech acquisitions like Scale AI.