Prediction Markets are Dangerous

Encouraging instability at an institutional level seems like a bad idea?

If medicine is our weapon against disease, and engineering our weapon against nature, then finance is our weapon against time. You can look at every part of the modern financial ecosystem and boil it down to an attempt to predict the future. Warren Buffet is, in some sense, the world’s greatest fortune teller. This despite his famous quote that “the only value of stock forecasters is to make fortune tellers look good.” We may not be able to see the tapestry of probable events that Paul Atriedes / Tim Chalamet can see,1 but between all of our financial institutions we can get pretty damn close.

What is the core of finance? To buy low and sell high. When you buy a stock, or an option, or an oil field, or ten trucks of corn, you are making a prediction about the future. And then you get rewarded if you are correct. Our financial system incentivizes people to come up with better and better forecasts of the future. The folks over at Jane Street pay hundreds of thousands of dollars for the best meteorologists in the world to analyze cloud data in Tibet so they can predict what will happen to Indian and Chinese commodities weeks and months later, while the quants at Citadel are ingesting satellite data to see which factories have trucks rolling out and which ones don’t so they can predict supply chain issues a year out.

This information ends up disseminating through the market. When Jane Street sells all of its Indian commodities, they are sharing their prediction about the future, which in turn is reflected in the price. So anyone in the world can eyeball the price movements of an asset at any time, and from that predict all sorts of interesting things about what may happen and why. Collective wisdom emerges from the populace’s shared interest in making money..

It’s not perfect. The markets can be wrong. But there is some truth in the semi-viral WallStreetBets post Everything is priced in.

Don’t even ask the question. The answer is yes, it’s priced in. Think Amazon will beat the next earnings? That’s already been priced in. You work at the drive thru for Mickey D’s and found out that the burgers are made of human meat? Priced in. You think insiders don’t already know that? The market is an all powerful, all encompassing being that knows the very inner workings of your subconscious before you were even born. Your very existence was priced in decades ago when the market was valuing Standard Oil’s expected future earnings based on population growth that would lead to your birth, what age you would get a car, how many times you would drive your car every week, how many times you take the bus/train, etc. Anything you can think of has already been priced in, even the things you aren’t thinking of.

(Note: not financial advice)

Though bankers are a favorite punching bag, I think the folks working in finance are doing an important job. It is really valuable to be able to predict the future. I think it makes the world a more stable place. People want to make prices go up, so they want to do things that create value and reduce things that destroy value. Even the most authoritarian dictator has an eye on the public markets because of their and their cronies’ investments; if the markets tank because of something they do, they will likely chicken out.

Except, wait, that’s not right. Sometimes people don’t want to make prices go up.

In an unregulated market, executives and politicians and people in power have pretty strong financial incentives to tear everything down. The better a company is doing, the more money to be made shorting the stock. The safer a country looks, the more money to be made destabilizing the place with war. The financial ecosystem as a whole is composed of billions of individuals, each with their own wants and desires. The markets are a prediction machine that drives to averages. You make a ton of cash if a shit company gets better; but you also make a ton of cash if a great company gets worse. The purely financial incentives stabilize somewhere in the middle.

So we try to leash the markets. We carve out certain kinds of trades as illegal. Fraudulent trades, misrepresentation, trading on insider information. If you’re a CEO and you buy a ton of shares in your competitor’s company days before you announce that you are going to set fire to your factories, you go to jail. We create ‘fiduciary duties’. Business executives have obligations to their company that are legally enforceable. As do lawmakers and members of the judiciary and so on. We do all this to ensure that our future prediction machines stay finely tuned, and we mostly succeed. You need the leash, even if it makes the markets less efficient, because the alternative is to encourage chaos.

I am against prediction markets, because prediction markets encourage chaos.

Prediction markets are a new kind of betting platform where individuals can bet directly on what is going to happen in the future. Generally, someone will pose a question, like “Will Dems take back the house in the 2026 midterms?” And the ‘crowd’ will trade shares marked “yes” and “no”. At some point in the future, the question will resolve. We will know, in November of 2026, whether the Dems have taken back the house. At that point, folks who have shares of the correct answer get a payout.

So people try to predict the future. In August of 2026, if it seems like the Dems are doing great, ‘yes’ shares will trade higher because people want the payout. And if it seems like the Dems are having a bad time, the ‘no’ shares will trade higher.

If this sounds like sports betting, that’s because it is basically the same beast. There’s a pretty smooth gradient between “I am going to put money on the 49ers because I think they will beat the Eagles” and “I am going to put money on Google because I think they will beat OpenAI”. Of course, there’s a lot of regulation around putting money on Google. And in recent years, there is a lot less regulation around putting money on just about anything else.2

This has led to a set of “prediction market companies”, including Kalshi, Manifold, Metaculus, and Polymarket.

Proponents argue that these markets will benefit people the same way financial markets already do. The steelman case is something like this:

Having accurate pricing is a good thing because it helps people prepare for the future;

When insiders share their information with the broader world, it results in more accurate pricing;

Therefore, incentivizing people with private information to bet on prediction markets makes everyone better off.

It’s a tempting argument, especially since people3 are already looking for sophisticated-sounding excuses to bet on things. The problem is, the steelman completely dodges all of the very real problems that come with incentivizing betting.

Here is an example. A few weeks ago, the Trump admin kidnapped Venezuelan dictator Nicolas Maduro. We can do a dozen rounds about whether or not this was a good thing, it’s not really relevant. What is relevant is that moments before Maduro’s capture was announced, someone went and bought a ton of shares on Polymarket saying that Maduro would be out of office before end of Jan.

The person in question made over $400k. Not the most they could have made if they were really looking to trade serious money. But a tidy sum to pick up entirely risk free.

This raises some questions. We don’t know who the guy was, nor do we know what role they played in the decision to capture Maduro. Most likely, it was some random grunt who heard the news by being in the right place at the right time. But there’s a specter of doubt — what if it was a member of the Chiefs of Staff? A member of the Cabinet? The President himself? We generally seek transparency in the wheelings and dealings of our political class precisely so that we can track skewed incentives. Prediction markets can skew everyone’s incentives, the same way as straightforward manipulation of financial incentives.

Free markets drive towards averages. Bad companies become better, but great companies become worse. What does that mean for stability? Despite the news, we live in one of the most stable geopolitical eras. Average life expectancy keeps going up, average wealth keeps going up, and poverty and child mortality and so on keep going down. Prediction markets add financial pressure to reverse those trends. Tomorrow, someone could put up a prediction market on the likelihood of a wolf attack in a major French city. This is an extremely unlikely event, so most people will bet against it. Which, of course, means there is now a massive financial incentive for someone to go and release a bunch of wild wolves on the streets of Paris. Or, put a slightly different way, there is never going to be another American invasion or police action that doesn’t make some Pentagon guy rich enough to buy a boat.4

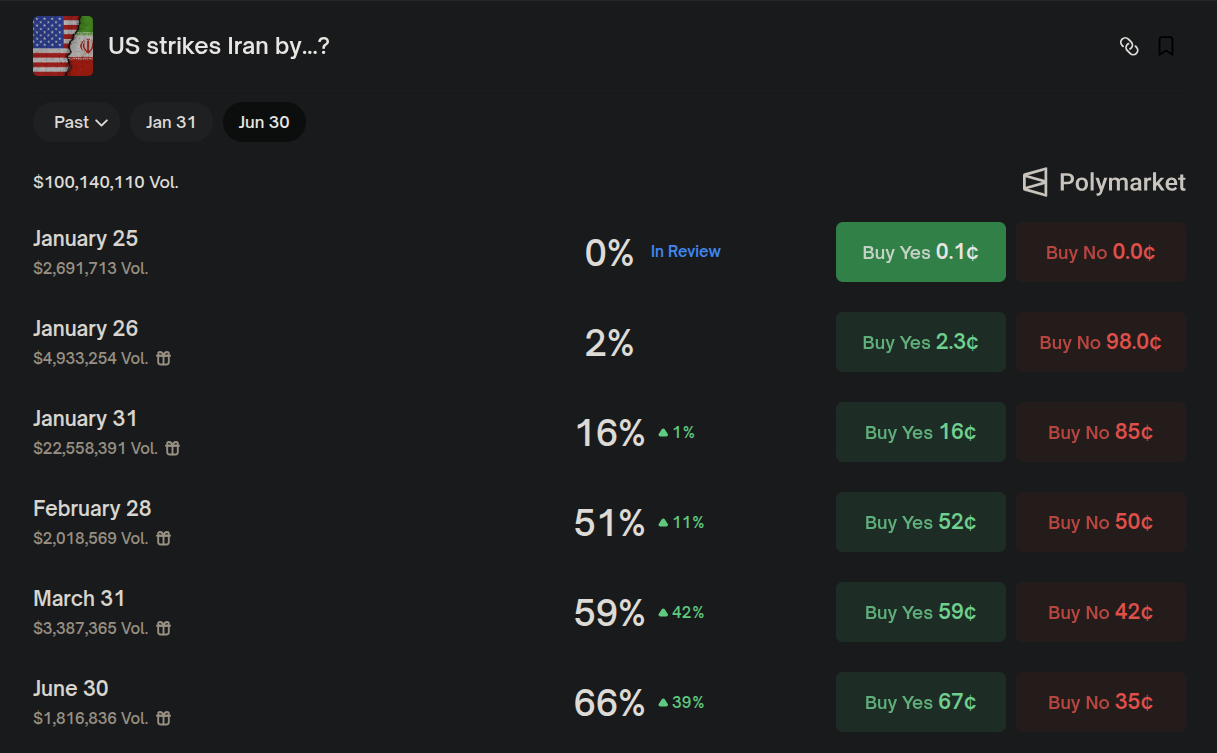

Take a look at some of the markets on these sites. US strikes in Iran:

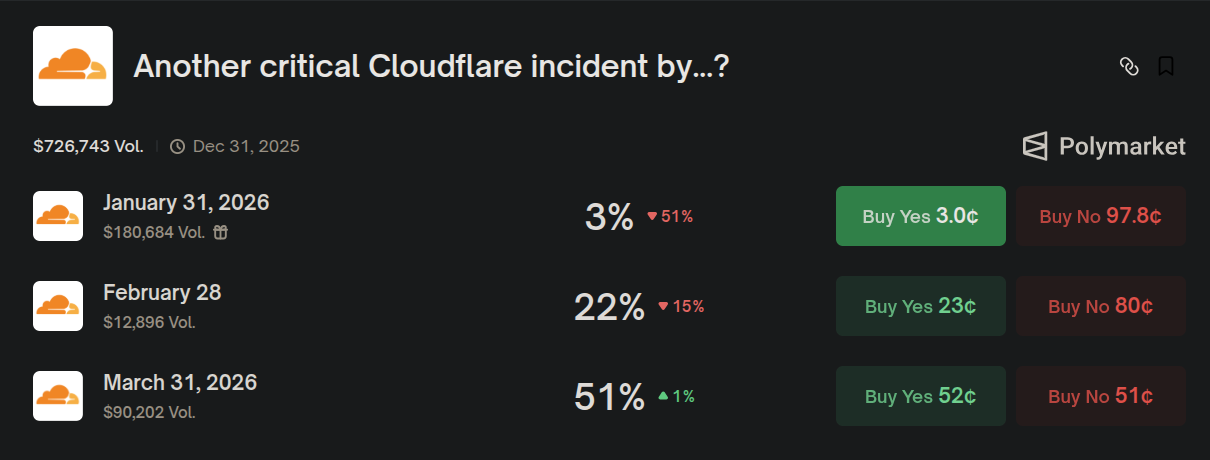

Cloudflare critical incident:

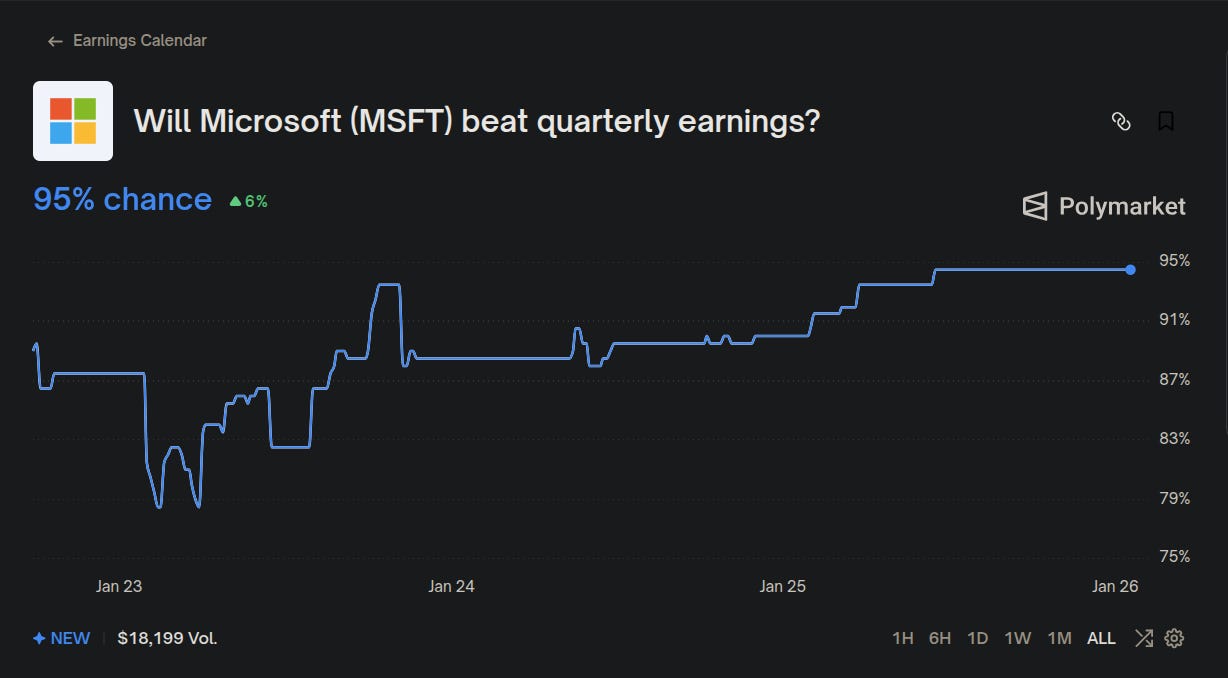

Bets on earnings:

No one cares about, like, a betting market on whether Bad Bunny wears a skirt to the superbowl.5 But it’s scary to imagine someone with decision-making power having a personal investment in the market outcomes above. Maybe it’s just because I am in tech, but the cloudflare one seems particularly egregious. It just isn’t that hard for a single engineer to push malicious code! And if they do in the next week, they can make a guaranteed 28x return.

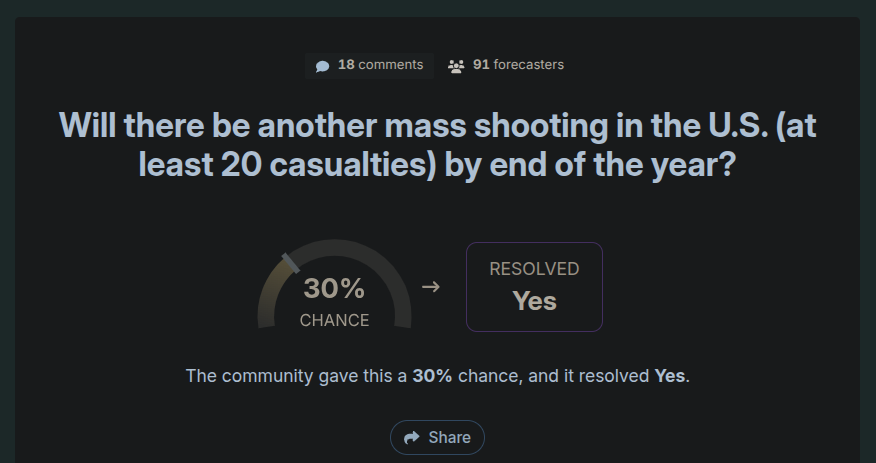

Insider trading laws are already tough to enforce. But historically, the number of decision makers who have a lot at stake is mostly pretty small. Prediction markets feel different in two critical ways. First, a lot more people can have a direct impact on a prediction market. Second, there are a lot more decisions that can now be directly traded on. This one-two punch means the surface area to cover is way higher. Before, it was pretty hard to ‘trade’ on your ability to create an outage on Cloudflare, even if a lot of people could or would do so. Now, anyone can make money off destabilizing behavior. It’s grim to apply the same thought process to, e.g., mass shootings.

From where I sit, prediction markets need a massive amount of regulation before I begin to feel good about them. But there are obvious low hanging things that we can do, like:

Deanonymize prediction markets;

Pass legislation or guidance indicating that prediction markets behave like securities;

Pass new legislation emphasizing that insider trading is still illegal

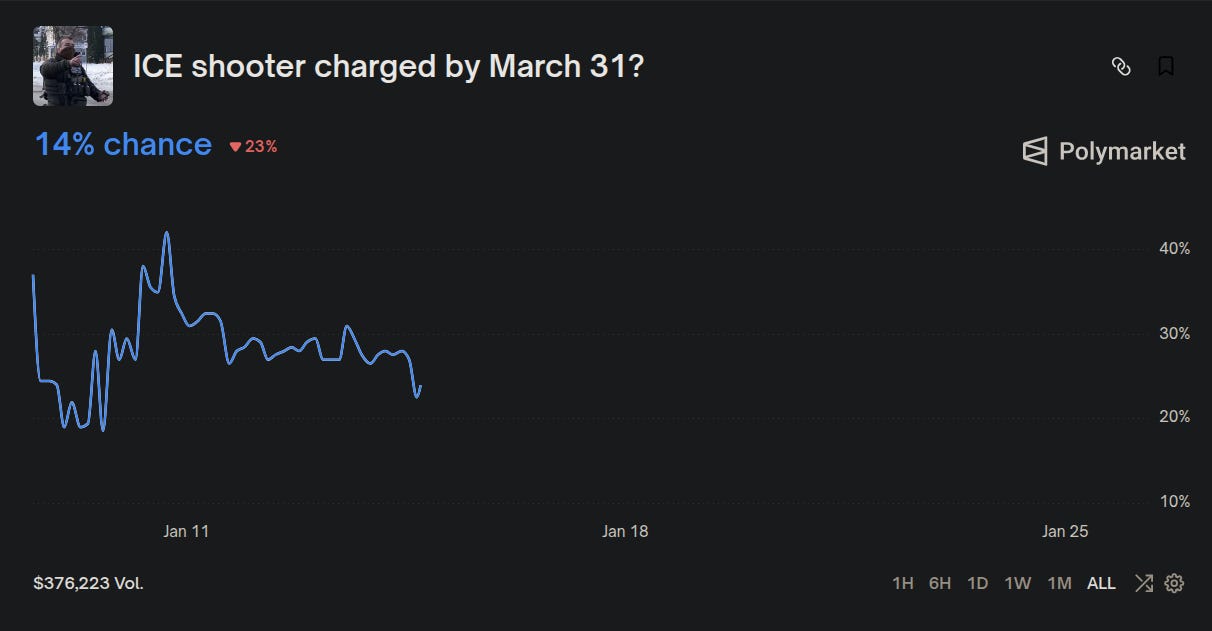

It’s weird to focus on this in the midst of everything else going on, but it all feels connected. There is no better symbol of the gamification and hyper-optimization of our lives than a platform where you are encouraged to bet your life savings on how many times Elon Musk will tweet in a given day. Or whether the ICE shooter in Minneapolis will be charged by the end of the quarter.

“The prescience, he realized, was an illumination that incorporated the limits of what it revealed- at once a source of accuracy and meaningful error. A kind of Heisenberg indeterminacy intervened: the expenditure of energy that revealed what he saw, changed what he saw.” — Dune

In 2018, the Supreme Court ruled in Murphy vs. NCAA that federal prohibitions on sports betting were a violation of states rights, and struck down previous laws that prevented sports betting across the country. I think my home state, NJ, was wrong for prosecuting this case. Sports betting really took off in 2020 when everyone was home with nothing to do.

I think the term is ‘degens’

Thank you “Neurology for You” for the particularly evocative example.

20% likelihood right now

Crazy. I was just writing a post titled "The Prediction Market Experiment Has Failed" with insider trading being one of the big problems.

I've spoken with people who are major advocates of prediction markets in their ideal form, to people building competitors to Polymarket/Kalshi, and to people who regularly bet on prediction markets for fun. My conclusion is that almost none of the original "theory" has borne out in practice, at least by trading volume. The overwhelming majority of trades on prediction markets are either gambling on information that has no value outside the market, crypto, or sports betting.

I’m a pretty liberal person in general, but my most conservative take is that gambling should just be flat out illegal. I understand that that’s not practical to enforce.

I used to hold to “it’s distasteful, but shouldn’t be illegal.” The last few years of the DraftKings-ification of everything has seen me swing around even harder; not just sports betting but the casino should be abolished as blights on civilization.

Prediction markets are an even more nakedly corrupt incarnation of the degen gambler impulse, which makes it all the more galling when they advertise themselves as *liberating markets for the little guy*

If Kevin Hart tells me about parlays one more time I’m going to lose it.