Movie Review: Thoughts on Lawrence of Arabia

What happens when things go too well?

If I had to summarize my review in a single line, it would be: “This is perhaps the greatest movie ever made.”

Spoilers, obviously.

One of the great things about living in NYC is its thriving cinephile community. There are so many independent theaters that are constantly running their own programming, supported by a vibrant collection of beanie wearing hipsters that all share a love of movies as a medium. Metrograph, IFC, Nitehawk. On any given day you can see anything from a cinematic classic to an indie art film, all as it was meant to be seen — on a gigantic projection with a big rumbling soundsystem, popcorn and soda in hand. I wouldn’t call myself a ‘metrograph girlie’, in fact I’ve recently let my Metrograph membership expire. But as a result of living in this city, I am now much more partial to seeing movies in their original format instead of on a tiny dirty laptop screen with a pair of shitty speakers (the reason we all need subtitles is because movies were not audio-mixed for stereo!)

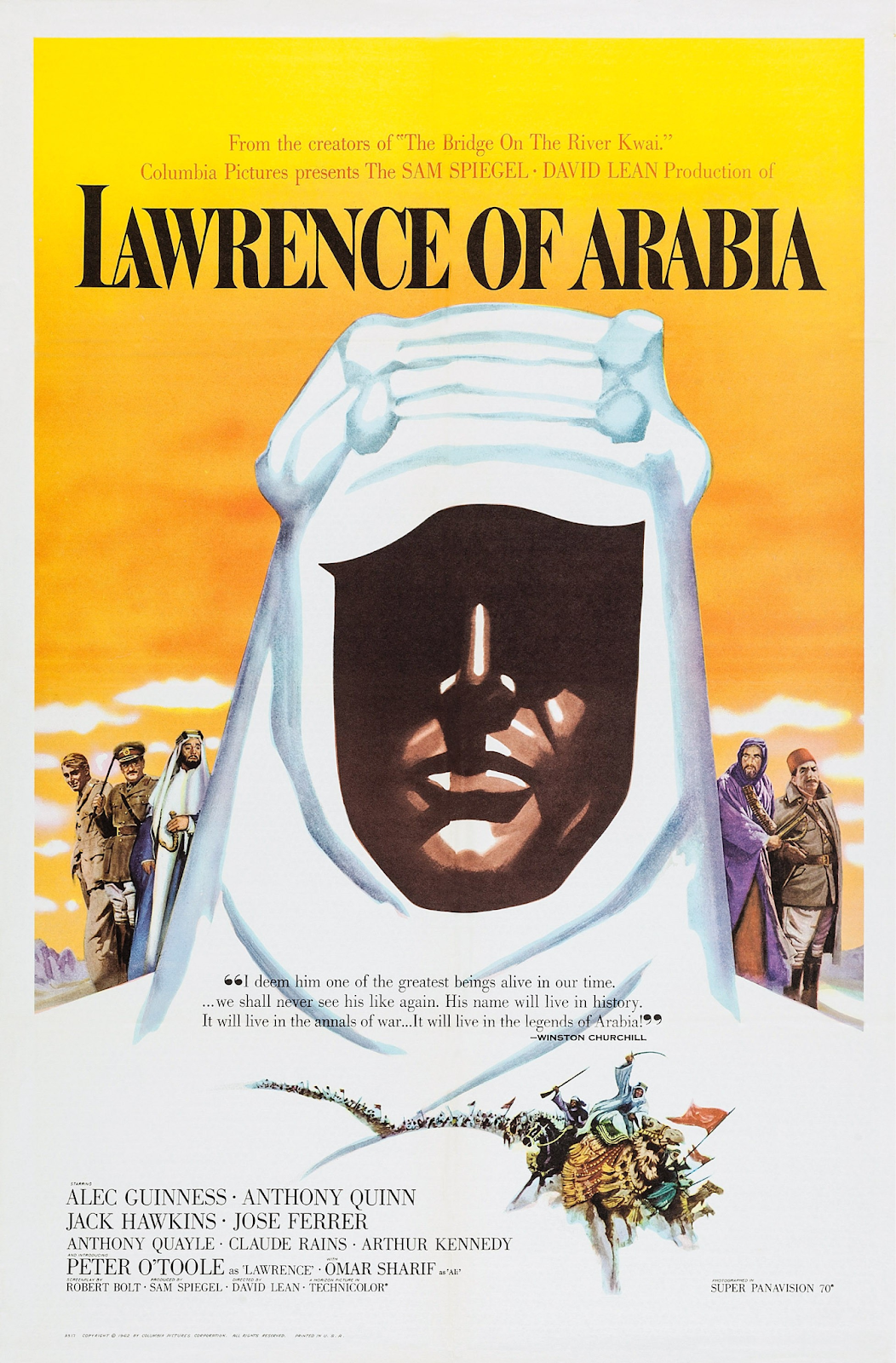

I’d heard a lot about the impact of Lawrence of Arabia. I’d heard that one of my best friends (also named Lawrence, no relation), himself a big cinephile, rates it as one of his favorite movies. I’d heard that it is well known as a masterpiece. I’d heard and read critical thinkpieces about how Dune, Star Wars, Mad Max, and even Marvel owe their existence to the sands of Arabia. And, of course, I’d heard that this movie must be seen in theaters if possible.

But I didn’t really know much about the movie itself. It’s about a guy, presumably named Lawrence. He spends time in Arabia. It’s about World War 1 maybe? It’s four hours long??? This was about all I knew when I decided to give up my Sunday evening in service of a 70MM showing at the Paris Theater.1

There are few things that I think are absolutely life changing. I don’t think that Lawrence of Arabia is one such thing. But it is simply the finest example of cinema as an art form that I have ever seen. If you have any appreciation for motion pictures and have not yet seen this movie, you are doing yourself a massive disservice.

First, the basic story beats. The plot follows T.E. Lawrence, a British officer during World War 1. The movie opens on his funeral. He is interred in St. Paul’s Cathedral (for the Americans, this is a big deal) where we oddly discover that many there who knew the man seemed to lack fond memories of him. We smash cut to Cairo, where a younger Lawrence is introduced as an eccentric but well educated Oxford graduate; we see him being shipped to Arabia to represent British interests in the war against the Ottoman Turks; and we see him landing among the Bedouin tents where he immediately seems to fall in love with the people, the culture, and the dream of a unified Arabia.

From here, a whirlwind.

We follow Lawrence as he initiates and successfully executes a near impossible attack on the Turkish city of Aqaba; as he returns to Cairo to negotiate for supplies on behalf of the fledgling ‘Arab’ revolt; as he begins a guerilla campaign against the Turks, destroying rail lines while rapidly becoming a populist idol. We watch as he falls to his own hubris in an ill fated infiltration of Deraa that leads to his torture, and as he is easily manipulated by generals and statesmen to continue pushing into Damascus. And finally, we see Lawrence’s great fall, as he betrays his own principles when he participates in the brutal massacre of retreating Turks, followed quickly by his failure to achieve any semblance of Arab governance between the tribes he has martialed.

If it sounds like a lot, that is because it is a lot. The movie is truly an epic, in scope and scale.

This alone is not what makes Lawrence of Arabia a great film. There are many movies that are equally ambitious in their scope, and even a few others that execute on those ambitions successfully. What sets Lawrence of Arabia apart — what makes it a great film — is that it executes on every aspect of film making to an extremely high degree.

Film is a complicated medium, because it isn’t a single medium at all. It is an amalgamation of so many other forms of art. People go to the symphony and expect compelling music. People go to the gallery and expect beautiful paintings. People go to the stage and expect moving acting and writing and oration. When you go to the movies, you expect all of the above and more. Film is music and visuals and acting, narrative and costume and framing, editing and cinematography and movement. There are good films that excel at some of these things. But any great movie lives and dies on the synthesis of all of these parts into a greater whole. When I say Lawrence of Arabia is the greatest movie ever made, I mean it in this sense — that it is the best use of film as a medium, that it uses all of a movie’s constituent parts to create one spectacular whole better than any other film I’ve ever seen.

In isolation, each piece of Lawrence of Arabia deserves praise for its technical excellence. The soaring soundtrack that opens the film (playing for a full ten minutes before the curtains rise) is immediately iconic. Peter O’Toole and Omar Sharif are incredible actors who completely sell the audience on their commitments and delusions and struggles. The story is a compelling examination of politics and hero worship and megalomania; the screenplay manages to do justice to those heavy themes and still make the movie really, really funny.

And the visuals! Every single shot of this movie!

Like damn! I want to specifically call out the coloring, which just absolutely pops from the screen. Like, compare Lawrence to Tony Stark:

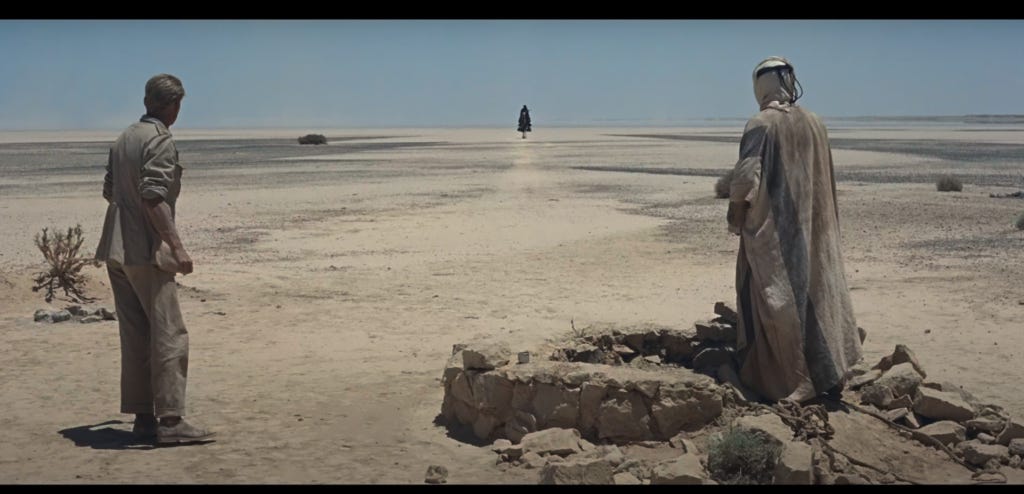

In motion, all these individually great components accentuate the others. For example, let’s take a look at this shot again:

The long, slow shots of the camel train through the desert and the brooding, ominous orchestral soundtrack combine to serve a narrative purpose. The audience is told that the trek is impossible and doomed to fail. The audio and visuals come together to make the audience viscerally feel that the trek is impossible and doomed to fail. The scope of the desert directly matches the scope of the undertaking. So when Lawrence successfully crosses the desert, we, the air conditioned urban audience who have never been to Jordan, recognize just how massive a feat it is — and why it immediately creates devotion in the men who crossed with him.

Or consider this iconic bit of editing:

That smash cut from Lawrence’s close up profile to the sun slowly rising over the desert is an incredible bit of editorial discretion. Lawrence, up close, baiting the fire to touch his fingers, stating just moments before to an awed audience that the trick is just to be able to withstand the pain of the fire on your skin. This is perhaps the most important line of characterization that we get of our protagonist thus far. From this single line, we learn that our man is not a normal person. He is willing to push himself to incredible lengths for performance, for the adulation of others, and for no reason at all. And then a jarring transition to the main antagonist of the movie: the scorching hot ball of fire in the sky that will torment our protagonist for the next three hours, silence leading to a crescendo of discordant strings as the sun slowly peeks out over the horizon. Here, the visuals, audio, and editing all come together to create an incredible sense of dread. The sunrise, normally a thing of beauty, becomes creeping, unsettling, dangerous. The shot of the sunrise serves no other purpose than to unsettle the audience — after a few moments we again transition, fading into a shot of a very small Lawrence coming over the desert dunes while the same string line resolves into the triumphant main theme.

Film is about association. Consider this famous interview with the incredible Alfred Hitchcock. If you have a shot of an old man smiling, and then cut to a shot of a puppy or a cute kid, we the audience understand that this is a wholesome experience. If you take that same shot of the man and then cut to, say, a half naked woman, we the audience interpret the exact same man as a leering creep.

The artistry of film making comes from the ability to weave the disparate mediums inherent to film into coherent, deeply instinctual associations in the audience. On purely visual terms, you simply cannot make that shot of the sunrise a negative thing. But add in the audio, the writing, the cut, and suddenly you can get your audience to associate that sunrise with fear. That’s movie magic.

Now imagine that level of detail in every scene, and you have Lawrence of Arabia.

Visuals and audio are easy to experience; what of the story? The characters and the writing?

Cards on the table, this kind of movie is like catnip for me. Mia jokes that I only like “great man” films, movies where singular individuals drive the entire movie through their sheer force of will, often against conventional wisdom. Feel good movies like Moneyball and Ratatouille are excellent examples of the genre. So are cautionary tales like Citizen Kane or The Godfather.

Lawrence of Arabia fits squarely in this category.

The main character, T.E. Lawrence, is a strange protagonist for what is essentially a war film. He’s eccentric, always performing in an over the top theater-kid kind of way. He’s kinda twiggy and soft looking. He’s an Oxford grad who talks about books. Why would you send this guy to foment revolution alongside Bedouin desert tribes?

Spend a day in the desert? He looks like he hasn’t spent a day out of the air-conditioned makeup studio! His military superiors mostly have the same doubts; at any rate, they certainly don’t think all too highly of him. And yet, by the end of the film, Lawrence has taken Damascus from the Turks and has become a major piece in the British Empire’s play for the region.

As in many other “great man” films, the protagonist has a seemingly endless ability to warp reality. Impossible things become possible; Lawrence himself says, “Nothing is written.” Whenever there is a character that strong on screen, the plot itself becomes a forgone conclusion. And so the movie itself must turn inward. “Great man” films are rarely about what the man did. Rather, they are about who he was.

This is why the movie opens on an eager reporter asking everyone at the funeral the singular defining question of the film: “who was Lawrence of Arabia?”

It’s a tough question, in part because Lawrence changes a lot over the 4 hour run time. The movie has a three part structure, each part punctuated by Lawrence returning to and leaving from the British Headquarters. Each time he leaves, he is a different person. He starts as an idealist, believing in the Arab cause; he becomes a megalomaniac, believing in himself as god; he ends a broken shell, believing in nothing at all.

To me, the story is primarily a cautionary tale of the strange corruption that comes with being too successful. What happens to a smart man, an idealist and a scholar, when things go right one too many times? On some basic level, Lawrence of Arabia is about man vs nature or man vs man. After all, it’s a war story set in the desert. But the real conflict is man vs self.

Perhaps the most obvious — and shocking — example of this theme comes when Lawrence first returns to Cairo after his success at Aqaba. By now, we the audience have the sense that something is not quite right with Lawrence. Not just in the sense that he’s been traumatized by death and violence; rather, that the endearing idealist that won us over at the beginning of the film is maybe no longer fully present. Something darker has grown, sprouted from a seed. It manifests in the way Lawrence talks about himself,2 and the way he takes unnecessary risks.

Lawrence knows this, or at least is able to recognize that something is off. Which is why he ends up in General Allenby’s office, dressed in full Bedouin gear, asking for permission to leave the military. It is a moment of lucidity, the last bit of his original idealist self peeking through, desperate to derail the train from the tracks he is on.

Now we see Lawrence, utterly in the grip of his contradictions. His face works and he twists slowly about his chair as he gropes for words.

Lawrence: Well, I…let’s see now. I…killed…two people. I mean two Arabs. One was a boy…this was…yesterday…I led him into a quicksand. The other was a man — that was, oh let me see — before Aqaba anyway — I had to execute him with my pistol. There was something about it I didn’t like.

Allenby: Well naturally.

Lawrence: No. Something else.

Allenby: I see. Well that’s all right, let it be a warning.

Lawrence: No. Something else.

Allenby: What then?

Lawrence: I enjoyed it.

Consider the inherent contradiction here. He didn’t like that he liked it. Lawrence is at this moment at war with himself. In the first act of the movie, we get to know the good side — the version of Lawrence who defends the weak when he has everything to lose and nothing to gain, who befriends orphans and defends the honor of his dead friends. Here, there’s this new part of Lawrence. It’s hungry, and ambitious, and ruthless. It is obsessed with power. And it believes in its own ability more than anything else, to an unnatural and unhealthy degree. Why does this part of Lawrence enjoy killing Gasim, the soldier he just saved (at great risk) from the desert sun? Because it makes him god. Lawrence saved Gasim and then killed him; he held the man’s entire life in his palms, twice.

Allenby convinces Lawrence to stay the course by appealing to that same powerhungry egoistic part of him. The result is catastrophic for Lawrence, because he keeps on winning. His guerilla war tactics are a massive success. His war-time victories bring riches to his mob and adulation and accolades to himself. He becomes world famous. And every success further entrenches his megalomania. When Lawrence survives being shot, you can practically see his brain break. If at first he wondered whether he was beloved by god, now he knows. T.E. Lawrence is but a man. Lawrence of Arabia is immortal.

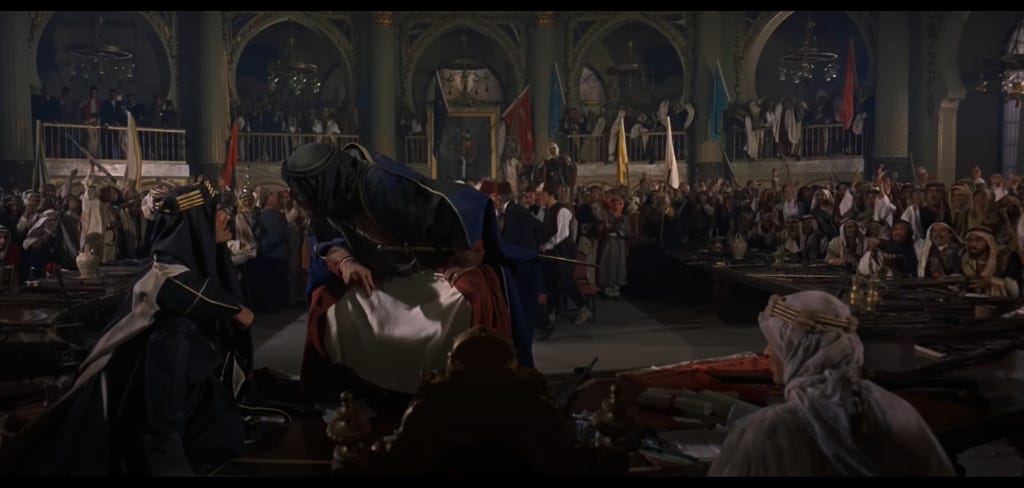

Pride goes before destruction, and a haughty spirit before a fall. Against council, Lawrence waltzes into Deraa believing he will simply not be caught and single handedly turn the garrison. He ends up beaten, tortured, and (it is heavily implied) raped by the Turks. The trauma turns him into a darker, more violent figure. He becomes more violent, and increasingly less able to lead. By the time he reaches Damascus, the mob is fully out of his control. In the one moment where Lawrence needed to succeed — at the first meeting of the Arab Council — he utterly fails to bring ‘his’ people together. So ends Lawrence of Arabia and the Arab Revolt.

Lawrence is a tragic figure, because he is clearly a great man. He is able to do things that everyone from his superiors to his allies to his enemies think is totally impossible. He could have changed the world. But he knows that he is destined to change the world; and as a result it all goes to his head, and he becomes extremely easy to manipulate. Obviously, Lawrence ends up doing the British Empire’s dirty work, betraying his own ideals of Pan Arab nationalism in the process. But he also ends up being manipulated and used by the very Arab tribes that he was supposedly working for. In one of the most damning scenes of the movie, Prince Feisal sits down to negotiate with the Allenby for control of Damascus and immediately gives up half of what Lawrence fought so hard to claim for the Arabic cause.

Lawrence completes the closing of the door.

Feisal: The powerhouse, the telephone exchange, these I concede. The pumping plant I must retain.

Brighton looks at him, horrified and indignant.

Feisal: The world is delighted with the picture of Damascus liberated by the Arab Army.

Allenby: Led, may I remind you, by a British serving Officer!

Feisal: Ah yes. But then Aurens is a sword with two edges. We are equally glad to be rid of him are we not?

Allenby (between admiration and disgust): I thought I was a hard man.

It’s hard not to be aghast at this revelation from Feisal, who comes out looking like a total snake. But this revelation raises a huge question: who was Lawrence fighting for? Who even wants a unified Arabia? For the vast majority of the movie we are led to believe that it’s Feisal and his cause, yet here we see that even Feisal wanted the guy gone. This scene is so potent because it lays bare how little Lawrence actually accomplished. Over the course of four hours we watch this singular man succeed over and over again, winning battle after battle, just to completely miss the big picture and lose the war. Everything he works for, immediately traded away. The people he supposedly came to help, dismissive and uninterested. Lawrence suffers real loss and trauma, and in the end absolutely nothing comes of it. He is a pawn, used in other people’s games.

There are a lot of things I loved about how the story is told, that I wish I could spend more time on. I’ll mention some others briefly here.

In an early draft of this review, Sherif Ali was far more prominent, and even though I do not dwell on him as much in this final publication he is perhaps my favorite character overall. If Lawrence is the lead of the film, Sherif Ali is the second chair. You cannot understand Lawrence except through the lens of Ali and vice versa. Over the course of the movie, Ali and Lawrence switch ideologies. When we first meet Ali, he has just killed Lawrence’s guide, Tafas, and Lawrence chews him out for it. What makes this moment so important is the cultural distance between these two men. Lawrence is an outsider in every way, from the food he eats to the clothes he wears. Yet he is the one holding onto the banner of Arab pan-nationalism. It’s never made clear why. It seems that Lawrence sprung from the womb with a deep belief that these people should be a people. Sherif Ali has no such pretensions, an irony that is further underscored when we discover that he is chief advisor for Prince Feisal, the leader of the Arab revolt and the man Lawrence was sent to aid. But we get to watch Ali grow. He begins to see the vision; he starts to learn about politics; he puts aside his petty tribal feuds. By the end of the film, it is Ali who attempts to hold back Lawrence from a murderous rampage, begging Lawrence to remember the cause so they can make it to Damascus before the British. Everything depends on this — if the British get there first, the ‘cause’ is finished. But Lawrence, overcome by tribal bloodlust, chooses to fight instead. Ali too is tragic, but in a different way. In Lawrence, we see a great man who failed. In Ali, we see what might have been had Lawrence succeeded. Ali represents the cost of Lawrence’s insanity.

Speaking of insanity, I loved the visual contrast of the train robbery against Lawrence’s high minded moralistic idealism. Lawrence’s advisors continually warn Lawrence that his army is not interested in discipline or unity. They are clearly raiders and mercenaries who desert the moment they get enough loot to carry. Lawrence, by contrast, insists that they are freedom fighters, that they are motivated by creating and building a country. It’s a great way to show that Lawrence is completely losing his grip without explicitly telling the audience. There is a moment when, talking to Brighton, Lawrence becomes deadly serious that he is going to give the Arabs their country. And I think it’s a fantastic moment, because everyone in the audience goes, “O, this guy really is totally blind isn’t he?”

The movie does a fantastic job showing just how hard it is to build things. War is, in some ways, easy. Point gun, click, boom. You can bring together a wide coalition of otherwise incompatible people by simply promising them the loot. Nevermind that looting requires destruction; nevermind that destruction is so much easier than creation. Lawrence deludes himself into believing that he’s building something real, but he never really has to broker long term compromise between his factions. Despite the repeated disdain from the soldiers in the movie, it turns out that politics is both important and extremely difficult. The only person who takes it seriously is Ali. But alone, he cannot build a government. By the time the mob reaches Damascus, the holes in the story are visible for everyone. And as the city falls apart under the rule of the completely dysfunctional Arab Council, it quickly becomes clear that Lawrence had built his castles on pillars of sand.

My last thought is a simple passing one — I couldn’t help but see some of the modern titans of industry reflected in this movie. I think you could make a 21st century version of Lawrence of Arabia with Elon Musk as the main character. Honestly, the story beats wouldn’t even be all that different. You’d just have to replace a war in Arabia with, like, San Francisco house parties.

I have so much more to say about this but I’ll stop here.

I really loved this movie. I think it is a triumph of the medium. Frankly I am sad that I will never get to watch this movie for the first time again. I think this will likely be the best movie I will see all year. Now if you’ll excuse me, I’m going to listen to the score on repeat.

70MM refers to the film format the movie is screened on, literally “70 millimeter”, a measure of the width of the film tape. Most movies that you are familiar with are likely filmed in 35MM. 70MM gives higher resolution and a wider aspect ratio.

Auda: Ten days? You will cross Sinai?

Lawrence: Why not? Moses did.

Auda: And you will take the…children?

Lawrence’s figure is already dim. His voice sails clearly back to Auda.

Lawrence: Moses did!

Auda: Moses was a prophet! And beloved of god!) and in the way he approaches risk (riding directly into a sand storm just because