Loyal and Longevity

On aging dogs and immortal flatworms

I. Maybe this is somewhat unexpected, but before I was doing a lot of AI research I was doing a lot of molecular biology research. Primarily oncology, though later a bit of neuro research. Even got published! The main reason I was doing oncology was because it was a route to doing longevity research — that is, a way for me to study aging and how we can slow aging down.

Some people say that the beauty of being in highschool is that you don't know how difficult things are, so you can't help but aim high. I knew a few folks wanted to go to Mars. I knew a TON of people who wanted to overthrow the concept of capitalism. I, of course, was always the pragmatist, and was very reasonable about my long term goals. In high school, I wanted to kill death, by finding a way to prevent death by aging. I distinctly remember announcing in a presentation that immortality was achievable within my lifetime. Hell, I even gave a TEDx talk on "the death of Death".

Now, you might think that this story ends with me realizing how silly I was, and (like the rest of my anti-capitalist friends) settling down into a job in middle management at a hedge fund. But actually, I'm still pretty excited about immortality and see much of my work in AI as an extension of that dream. I just don't get to talk about the aging stuff much, since everyone is on the hype train for automatic text completion.

That said, while OpenAI was busy distracting everybody with boardroom shenanigans, something big happened in the longevity world. A few days ago a startup called Loyal announced that they had received early FDA approvals for a drug that increases lifespan in large dog breeds. Their drug, named LOY-001 (probably pronounced loyool I guess?), was not indicated for cancer, or bone disease, or some other thing. The drug, and the trial, were explicitly about slowing down aging. I'm really really pumped about this, so I want to spend at least one blog post talking about what longevity research even is and why this announcement is so cool.

II. Aging is a funny thing. It's ubiquitous. We experience it every single day. Some of our strongest and most prevalent cultural institutions are about aging, and death, and how we grapple with these things. And so we assume it's inevitable, that we will all eventually die because that's just how it works.

But like, why? Imagine you were some sort of manifestation of the concept of evolution. Your goal is to create an organism that survives and spreads as much as possible. So of course you create a clock, after which your organism can't have kids. And also, after some other later clock, your organism ceases to exist. Very reasonable!

I suspect most people have never really considered why we age, or what happens under the hood. Turns out, it's not magic. One of the most important lessons in molecular biology is that everything is causally dependent on protein expression. And I really do mean everything. To a first approximation, you can see things because your eyes express "seeing" proteins, and you can hear because your ears express "hearing" proteins. And you age because your body expresses "aging" proteins.

We solve a lot of problems in modern medicine by introducing proteins to the body in the right place at the right time. Sometimes those proteins are used to trigger other interactions — for example, lactase pills that are used to digest dairy products. Sometimes, those proteins are used to block or inhibit other proteins that are behaving erratically — for example, most vaccine antibodies.

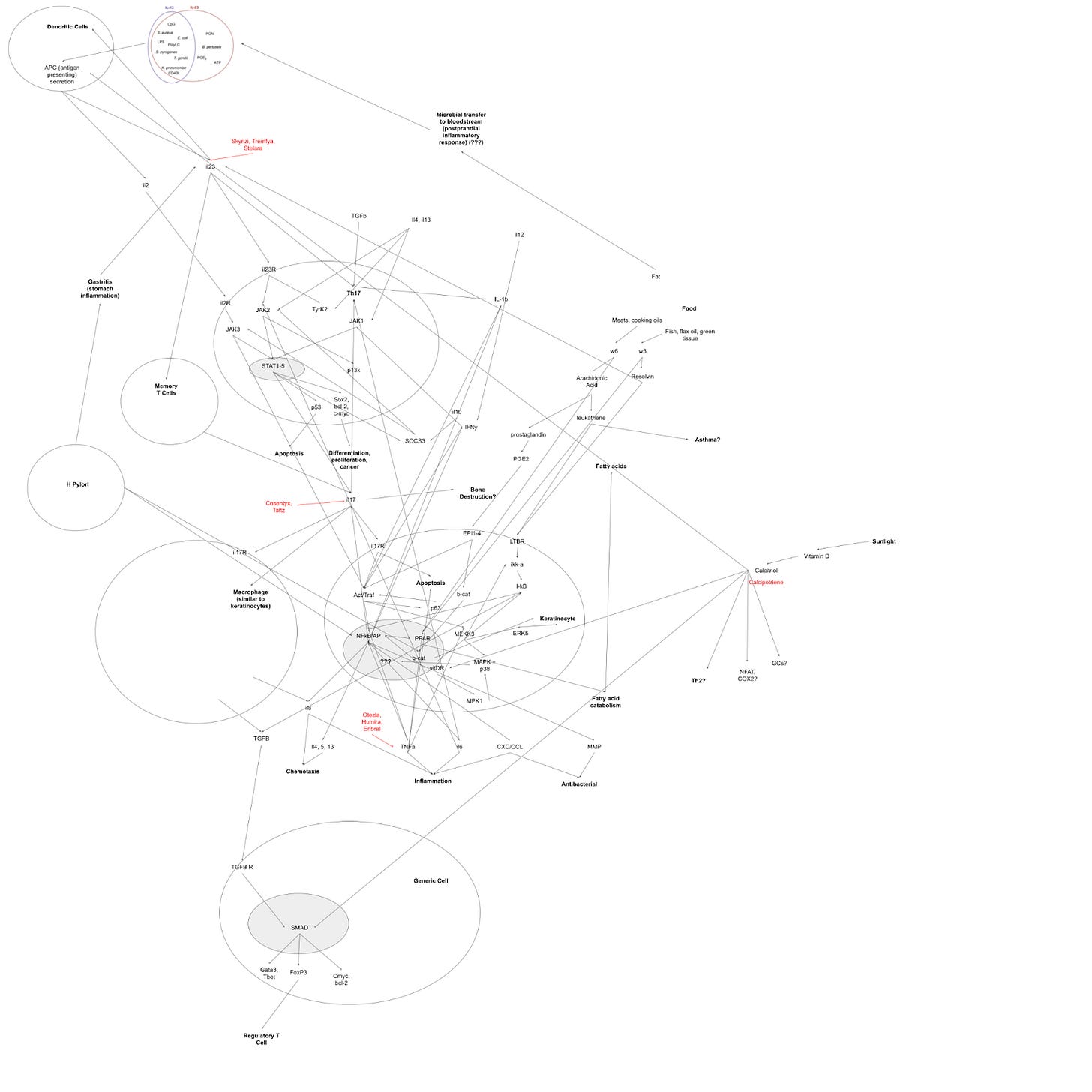

Sometimes we don't actually know the full scope of what a protein might do. I take a medicine called Skyrizi for my psoriasis. It's an antibody that blocks a protein called Interleukin-13. It is, by all accounts, a miracle of modern science. Here is a very rough outline of all of the pathways it may interact with:

Kinda complex! We don't really know why Skyrizi even works.

Psoriasis is likely genetic. It's caused by many interlocking factors. People who have the wrong mix of genes are born with psoriasis, for them it's inevitable. And because there was no cure, people developed all sorts of cultural and social norms on how to deal with it. I remember sitting in bed one day, covered in thick flaky itchy plaques, browsing the r/psoriasis Reddit and making peace with the fact that I might just be functionally disabled for the rest of my life.

And then one day a company called Abbvie released a drug called risankizumab and this problem — my problem — just went away.

Hopefully the metaphor is obvious.

III. Back to aging.

Like any other academic field, longevity research has its share of disagreements. There are always ongoing arguments about where funding should go and what promising approaches might look like. But I think everyone in longevity has the same basic insight that aging is a disease. It's one that everyone has, one that we're all born with, but it's a disease nonetheless. And like any other disease — like psoriasis — it can be treated if we can find the right protein pathways to push.

This becomes more obvious when we start looking outside of humans. There are a ton of other animals with much longer lifespans:

Tortoises have a natural lifespan that goes up to 150 years.

Some whales and sharks can get up to 200+ years.

There's a clam that was dated to be 500+ years.

And there are weirder animals, that are effectively immortal:

Naked mole rats don't show increased mortality from age. Aging is generally bad because it makes you more susceptible to something else that kills you. Naked mole rats…don't have this problem? Somehow? (They are also incredibly resistant to cancer, and can survive for a long time without oxygen???)

Turritopsis Dohrnii are a type of jellyfish that grow up into adults and then basically turn themselves back into babies. They literally Benjamin Button themselves back into youthfulness.

Planarian flatworms are like the Wolverine of biology. You can do anything you want to these guys, up to and including cutting them in half, and they will just keep on keeping on. Actually, it gets better. If you cut one in half, you get two fully functioning independent flatworms.

In this broader context, it's not really obvious that humans are fated to die somewhere between 80-100. So what is going on under the hood that makes our bodies different from the worm-jellyfish-rat? Turns out, we have some good guesses. Twelve, to be exact. From the seminal Hallmarks of Aging (2013):

We propose the following twelve hallmarks of aging: genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, disabled macroautophagy, deregulated nutrient-sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, altered intercellular communication, chronic inflammation, and dysbiosis.Obviously a lot of jargony words here. Still, the high level is that aging in many species manifests in the same basic ways — things become unstable and break down over time, repair systems stop functioning, and our cells stop replicating.

IV: It might be worth diving into one of these as an example, to get a sense of what aging actually looks like at the cellular level. Say, telomere attrition.

Imagine I had a string of yarn. The string is composed of a bunch of threads, all tightly wound around each other. The center of the string will be reasonably tight and stable. But unless I take special care, the edges of the string will fray, which will eventually cause the whole string to unravel.

We solve this issue with a cap on the end. For example, shoe laces all have aglets to prevent the eventual unwinding of the thread.

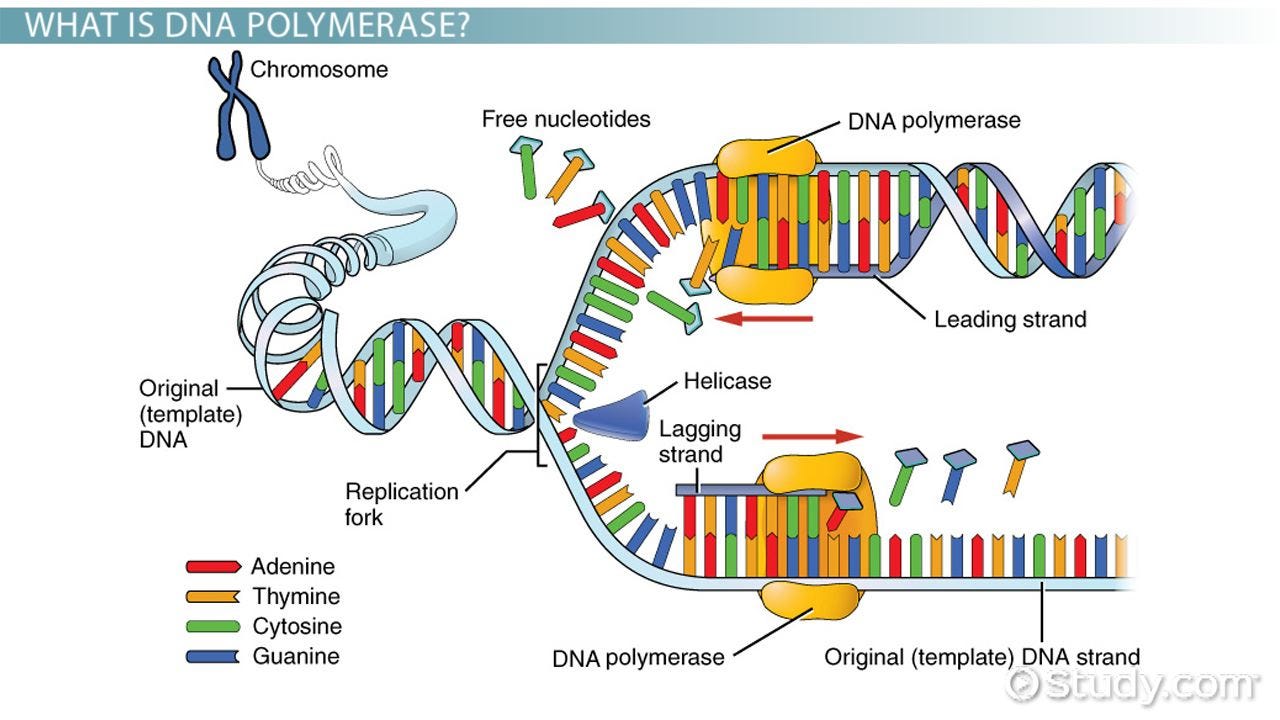

DNA is kind of like the string above. DNA is composed of two threads, tightly wound around each other to create the double helix we know so well. And it too has a cap: a telomere. A telomere is a repeated sequence of DNA that lives at the end of the DNA strand. As far as we know, telomeres aren't used for 'useful' information. They exist only to protect the DNA strand from damage.

A quick trip back to highschool biology. When a cell replicates, the DNA is also replicated. A protein (everything is a protein!) called helicase "unzips" the DNA, while another protein called DNA polymerase runs along the now-exposed DNA strand to create a copy.

Every time a DNA strand is copied, it loses a bit of information at the ends. Very roughly, this is because the DNA polymerase needs to end somewhere on the exposed DNA strand, and the area directly under the ending point isn't copied correctly. We really don't want to corrupt the actual DNA strand, so instead we have telomeres that degrade a bit each time the cell replicates.

This means that there is a natural limit on the number of times a cell can replicate, which is in turn determined by the length of the telomeres that you have. Longer telomeres = more cell replication = more youth. Unfortunately the human body doesn't have a mechanism by which we can increase the length of our telomeres, so we're doomed to an inevitable death.

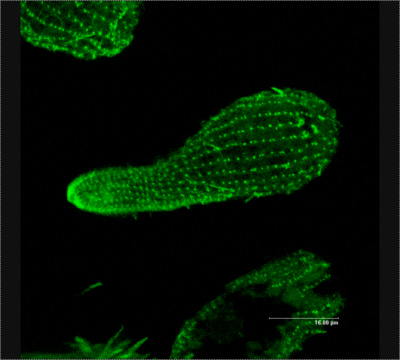

But this guy does!

That's a tetrahymena, a widely studied single cell organism that, among other things, produces a protein called telomerase. As the name suggests, telomerase operates on telomeres — actually, it explicitly makes telomeres longer.

Thank you mother nature!

So now we just go ahead and inject telomerase into our bodies, and then we live forever. And in fact, a bunch of researchers clearly had the same thought. And they went out and got a bunch of funding, and then used that funding to get a bunch of mice, and then bred those mice to produce a bunch of telomerase naturally, and then gave each other high-fives.

And then all those mice got cancer and died.

What the fuck?

V: This is where some of our abstractions break down. So far we've been talking about immortality at the 'person' level, as in "I, Amol Kapoor, will live to be a billion". But I, Amol Kapoor, am not made of a single organism. In fact, I'm made of trillions of cells, all of which are forced to work in harmony by a very very delicate ecosystem. If I want to be immortal, all of my cells need to be immortal too.

And, well, there's a reason we do oncology research on immortal cell lines.

Cancer cells are those that exhibit abnormal growth, they never stop dividing and can proliferate indefinitely with the right resources. They go rogue, stop cooperating with the other trillion cells in the system. Luckily, the human body has a ton of mechanisms to stop cancer cells. Some are reactive. For example, as cells begin to misbehave, our immune system kicks into gear to try and kill them off. And some are proactive. For example, every cell has an internal clock that prevents it from dividing too many ti — ah fuck.

Earlier, I asked how to create an organism that survives and spreads as much as possible. But this question is a bit misleading. We aren't trying to create a single organism that can survive and spread. We want to create a collective of some 30 trillion organisms that can all survive and spread together, but not so much that any one of them starts killing off the others.

It turns out that it's really hard to coordinate 30 trillion of anything. And so, we get aging. In this context, the limited lifespan of a telomere is a feature, not a bug. Virtually every attempt to revert any of the hallmarks of aging have led to mice-full-of-tumors. And the more I dove into oncology, the more I realized that what we call aging is really just a complex set of tools that our bodies have developed to keep cancer at bay.

I eventually gave up on ever finding a biological solution to aging. That's why I went into connectomics and later AI — I figured that we'd have a better chance cloning our brains onto silicon instead of trying to untangle our biology. But other people persevered, and some of them were actually moderately successful.

VI: And finally we're back to Loyal, and this magic drug that just successfully went through clinical trials for increasing lifespan.

This drug is important for two reasons.

First, because it works. I literally just spent some 2000 words explaining why longevity was hard and how reducing aging generally increases cancer. Loyal found a route that seems to neatly thread the needle.

The trick lies with a protein called IGF1. This protein is a "growth factor" — it stimulates cell reproduction and energy creation in order to help organisms grow big and strong. Dogs have it. Big dogs produce a lot of IGF1, small dogs produce less. Humans have it too, it kicks in around puberty and if you don't have enough of it for whatever reason you end up with the ominously named "failure to thrive" and possibly end up a few inches shorter than you'd have liked.

Having a lot of IGF1 is great when you're a teen. But when you're an adult, it's wasting energy and causing unnecessary replication. And here's the kicker: IGF1 causes cancer — cancer cells want to grow, IGF1 triggers growth, cancer cells like IGF1. So unlike most other aging therapies, reducing our IGF1 count also reduces our cancer risk1.

As a loving owner of two dogs, one who is now 10 years old, I am super excited that this drug works.

The second reason this drug is important is because it's a massive regulatory accomplishment. The FDA and other relevant health agencies don't consider "aging" a valid reason to take or prescribe drugs. As a result, anyone who was working on longevity had to do so under the guise of solving some other problem. This…kinda sucks? The best time to take drugs that stave off aging is when you’re young and healthy. They’re preventative. Hot take: if you can only take anti-aging drugs when you are sick with something else, and you get the anti-aging effects more or less as an accidental side effect, you’re not going to be able to effectively treat aging. Still, the FDA is a beast. For most pharma companies, the choice isn’t between treating aging the right way or the wrong way, it’s between “doing it the wrong way and getting FDA approval” or “not doing it at all”.

Loyal decided to tame the beast — they put together a massive, incredibly detailed plan for a set of trials to get approval for longevity specifically, along with data showing that their drug passed what's called a Reasonable Expectation of Effectiveness test. The final set of documentation was over 2300 pages (!). The FDA agreed with their results, granting approval for this section of Loyal's application. Quoting the announcement:

Today, I’m so proud to announce that Loyal has earned what we believe to be the FDA’s first-ever formal acceptance that a drug can be developed and approved to extend lifespan. In regulatory parlance, we have completed the technical effectiveness portion of our conditional approval application for LOY-001’s use in large dog lifespan extension.

As there was no established regulatory path for a lifespan extension drug, we had to design from scratch a scientifically strong and logistically feasible way to demonstrate efficacy of an aging drug. This process took more than four years, resulting in the 2,300+ page technical section now approved by the FDA. It included interventional studies of LOY-001 in an FDA-accepted model of canine aging and an observational (no-drug) study of 451 dogs.

...

From our data, the FDA believes LOY-001 is likely to be effective for large dog lifespan extension in the real world. Once we satisfactorily complete safety and manufacturing sections and other requirements, vets will be able to prescribe LOY-001 to extend the lifespan of large dogs while we complete the confirmatory pivotal lifespan extension study in parallel.Like many other government agencies, the FDA operates by precedent. If you can show a drug operates similarly to something else that was already approved, you'll have an easier time getting your thing approved. While Loyal still has to jump through a few hoops before vets can actually prescribe this drug, the hard part was the efficacy argument. In getting regulatory approval, Loyal has paved the path for other longevity medications, and I'm hopeful that many other pharmaceuticals can now make it to market for anti-aging.

VI. One last thing.

I think a lot of people are deeply uncomfortable with the premise of solving or curing aging. They don't see the dragon tyrant, or maybe don't want to. Cultural infrastructure can be hard to change.

But people love dogs. Anyone who's ever had and loved a dog wants to extend their lifespan. And that too is deeply wired.

My hope is that this announcement and accomplishment opens the floodgates for a cultural realignment around longevity research. That the anti-aging argument will start to make more sense. And that more research dollars will finally start to flow towards killing death for good.

This potentially raises a lot of other interesting questions that IGF1 raises, like "why do we have extra IGF1 as adults if it kills us?" The answer is roughly that there's less evolutionary pressure on things that happen after you stop having kids, generally around 30. IGF1 shaving a few years off the tail of your life doesn't impact how many kids you have.