Ilya's Papers to Carmack: Transformers

This post is part of a series of paper reviews, covering the ~30 papers Ilya Sutskever sent to John Carmack to learn about AI. To see the rest of the reviews, go here.

Paper 5: Attention is All You Need

High level

If you've been reading this series, I expect you are at least passingly familiar with this paper. Maybe you haven't read it all the way through, but you've heard the name. Or perhaps you've heard of one of the many many "X is all you need" spin-off papers. Writing a paper that gets a lot of citations is impressive. But writing a paper that is so important that the title structure becomes memetic? That's something else entirely.

"Attention is All You Need" is, in some sense, the culmination of years of work from a large chunk of the AI world, starting in 2014 when the original attention paper was published. Basically everyone knew that this attention thing was going to be critical for the future of neural networks. To quote Karpathy:

The concept of soft attention has turned out to be a powerful modeling feature and was also featured in Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate for Machine Translation and Memory Networks for (toy) Question Answering. In fact, I’d go as far as to say that

The concept of attention is the most interesting recent architectural innovation in neural networks.

(emphasis his)

But no one knows exactly how to really make attention work optimally! So there's ~3 years of iteration. Countless researchers try to stick attention into everything, and we get all manner of attention-enabled RNN architectures. Eventually, a few researchers from Google figure it out. They invent the transformer, a novel architecture building block. Over the next few years, the transformer becomes the swiss army knife of the AI world. It can seemingly do everything. Transformer architectures end up replacing convolutional networks in many vision tasks, and recurrent networks in virtually all language tasks. The transformer ends up becoming the backbone of all major LLMs, essentially powering the modern AI boom / bubble.

But of course, at the time of publication, the authors didn't know any of that. And as a result, “Attention is All You Need” is about a comparatively mundane task: how can language learning be parallelized more efficiently?

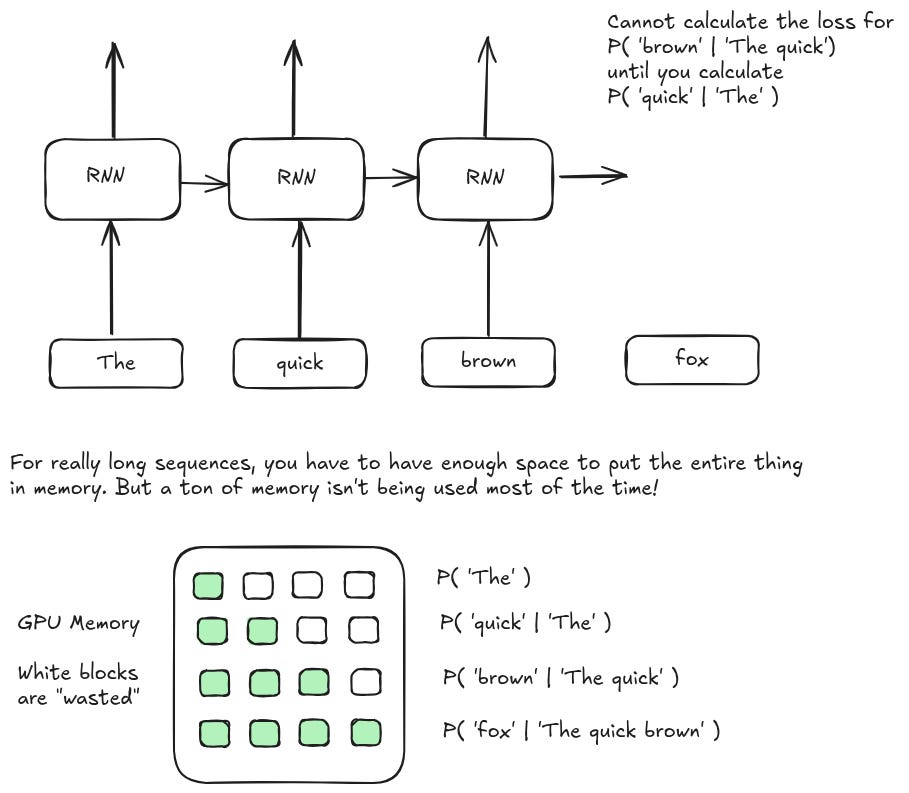

In 2017, the state of the art language models all required some form of recurrent architecture. These are pretty powerful (see here), and they use a constant amount of compute per token in a sequence which is great for inference speed over long contexts. But their fatal flaw is that they are, well, recurrent. If you have a really long sequence, you have to process each step in the sequence before you can process any future steps. That in turn means your wall clock training time is really constrained, because you can only fit so many long sequences into GPU memory. At the limit, you essentially have a batch size of 1. Not good.

So the number one goal of this paper is something like "make it feasible to train in parallel within a given sequence." For any auto-regressive task — text generation, translation, question answering, etc — this is really useful, because you can turn a single paragraph input into hundreds or even thousands of data samples without any labeling. This is something we discussed more in our review of RNNs:

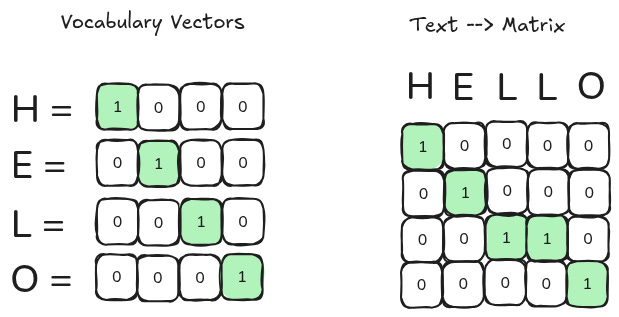

Here's an example program. Let's say you wanted to train a character generator: given some text, the model should predict the next most likely character in a sequence. Just to keep things simple, we're only going to look at 4 characters, 'h', 'e', 'l', 'o', and we're going to try to get the model to output "hello". Even though we only have one word, we actually have 4 separate training samples at the character level.

Given the letter 'h', the model should predict 'e'

Given the letters 'he' the model should predict 'l'

Given the letters 'hel' the model should predict 'l'

And given the letters 'hell' the model should predict 'o'

Because we are training a per-character generator, any amount of text can be broken down this way. You can get millions of samples from a single blog post!

The authors notice two things.

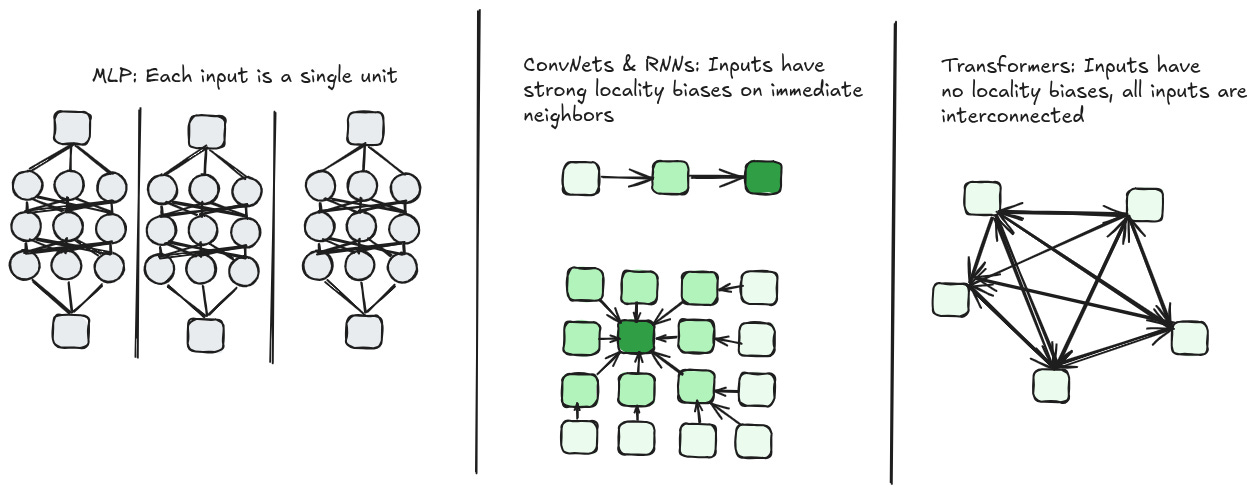

First, there exists a lot of literature that uses convolutional networks to try and solve language. These mostly work the way conv nets work for images — each token is given some kind of hidden representation, and successive conv nets decrease the resolution of the overall sequence by combining token representations that are next to each other. This is great because it's no longer recurrent. Your model can learn representations and transformations of those representations entirely in parallel. However, this naturally enforces a very strong locality bias, which means these things generally do poorly on long context windows.

And second, there is this exciting new thing called self attention that allows every part of an input matrix to "attend" to every other part of that input. The basic idea behind self attention is that if you use cosine similarity of two vectors as a weight for their "importance", the model naturally learns how to create an embedding space where relevant concepts (according to the loss function) are close to each other. Self attention takes that idea and applies it in an N^2 way — every input is weighted against every other input, producing a fully connected graph of weights that can then be used for other things.

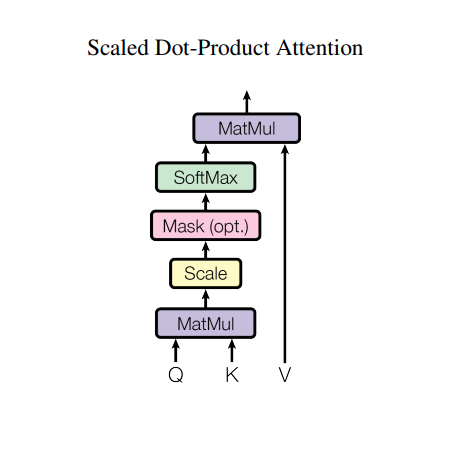

The big lightbulb moment is that self attention allows you to learn a "convolution filter" across the entire sequence at once. Or, using query/key semantics (first introduced in the original attention paper!), you can use each token to 'query' over all other tokens, get a ranked weighting for which other tokens are most important, and then aggregate those representations to construct new, weighted representations that pull in relevant data from across the sequence. Since there are no recurrent dependencies, you get long distance learning with complete ability to parallelize.

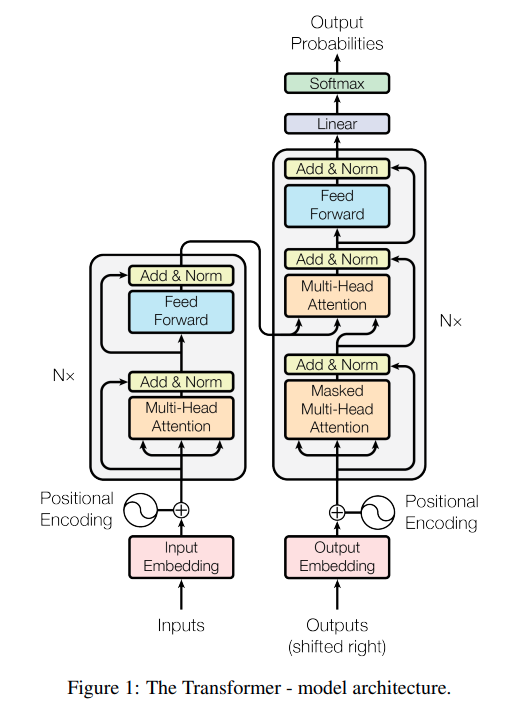

For some reason, the authors choose to use this as their model architecture diagram…

…which remains one of the most confusing model architecture diagrams I have ever seen. This is, of course, a beat by beat implementation of what their transformer block actually does in code-terms. Unfortunately, it leaves a bit to be desired in terms of how to understand the actual implementation. The key is that the QK matmul produces the ‘attention graph’ described above. Each attention graph is itself akin to a single convolution kernel, learning a specific relationship between different token representations.

From here, the rest of the model architecture roughly falls into place as the authors identify and patch issues with this baseline insight.

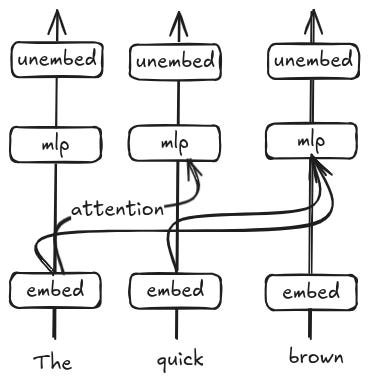

Standard practice is to take some form of hidden representation and pass it through a fully connected layer or two. No one has a great explanation for why this works, but the intuition is that the fully connected layers allow for unbiased and complete information mixing, where the model can learn operations on top of existing representations. So the authors throw a MLP on top of their transformer block. Importantly, the MLP is applied per-token, making the underlying architecture fundamentally about learning token-vectors instead of sequence-vectors.

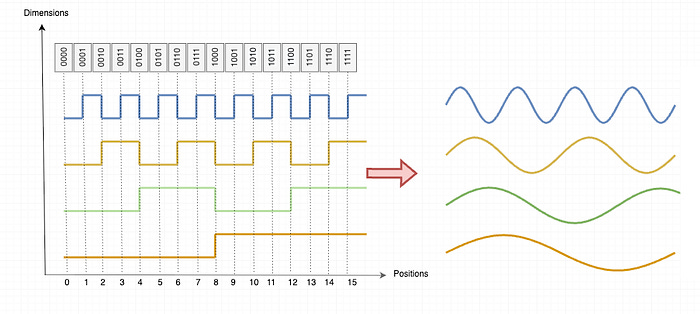

Attention is position agnostic. Each token is embedded separately from all of the others, so by default, the system has no way of differentiating between Barack Obama and Obama Barack. The authors fix this by appending a little bit of extra information that indicates the position ("positional encoding"). The positional encoding is a d-dimensioned vector, where each dimension within the vector is a sinusoid at a different frequency modulated by the position. This approximates a binary representation, while still being continuous.

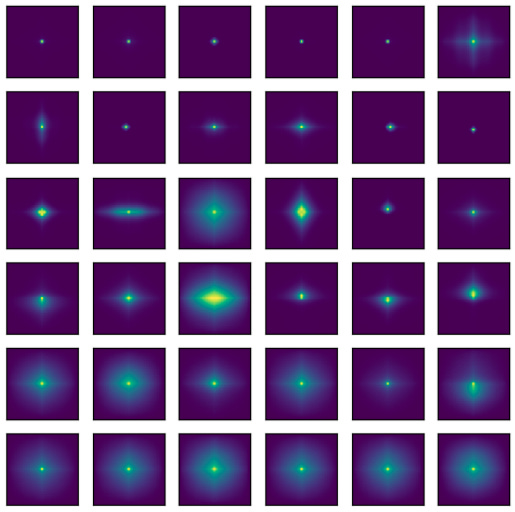

A single self attention weight matrix is akin to a single convolutional filter. The model isn't going to learn a ton if it has to pass all of its learning through this one bottleneck. So the authors use multiple "attention heads", essentially cloning the model a bunch of times to learn different operations in each head.

The authors are trying to solve an auto regressive translation task. Their new building block is great, but they don't particularly want to mess with the meta level architecture, so they use an encoder/decoder structure like everyone else at this time in this space.

And that's it for the architecture. Many of these smaller decisions have become the subject of quite a bit of research over the last few years, as every lab in the country turned their efforts towards squeezing every bit of juice out of these models. For example, here are a few papers on different positional encodings. But also, as is usual in the ML/AI world, a lot of things end up sticking around just because "that's what the original authors did."

As far as I can tell, despite many attempts, the core of the architecture has remained unchanged since the paper was released. Embed tokens. Create query/key/value vectors with an MLP. Matmul the query and key vectors to create a self attention matrix that indexes into the value vectors. MLP on top. It works.

The authors end the theoretical motivation of their architecture with a section amusingly named "Why Self Attention." Most of this section is about computational complexity, which again underscores how much this paper reads like an engineering paper rather than an industry defining theoretical innovation. The authors argue that self attention is good because:

Attention is cheaper than recurrence when the sequence length is less than the dimensionality of the hidden embedding state. In 2025 this is hilarious, since we have 1M+ token context windows. But back in 2017, the SOTA for context length was actually pretty small.

Attention is way more parallelizable, c.f. the conversation above about training samples and batch sizes.

Attention makes the path length between long-range dependencies in the network essentially constant (i.e. they aren’t “long-range” because every token is connected directly to every other token).

The rest of the paper is specifics about the transformer implementation and particular results on machine translation tasks using a variety of model hyperparameters. Nothing super interesting here, in my opinion.

Insights

When I first read the transformer paper back in 2018, I didn't really get it. The query/key/value framing was basically entirely foreign to me. I didn't understand why they were using search terms, how seemingly interchangeable embedding vectors could act as different things, or why they would need to use multiple attention heads (at the time, I wrote it off as a form of parameter hacking — a way to do better on benchmarks without actually, like, doing anything innovative).

Rereading the paper in 2025…I feel totally validated. This paper is, frankly, not super intuitive. I'd even say it's not that well written, but that's not quite right — rather, it's written for a very specific audience. I've said this before and I'll say it again: the authors of this paper clearly didn't set out to revolutionize the field of ML forever. They thought the audience for their paper was, like, a few dozen other nlp deep learning guys and the Google Translate product team.

The thing that helped me finally understand this paper is that the transformer is about token embeddings. Most of the recurrent nlp models we've discussed are, at some level, about sequence embeddings. They may start by embedding individual tokens, but eventually they merge the token data together to create some high dimensional sequence representation. The result is an informational bottleneck. By contrast, transformers keep token embeddings basically all the way through the stack. In fact, one way to think about transformers is as a series of columns, one per token, with a designated part in between where all the tokens connect and mix. I call this the 'token-centric' or 'representation-centric' view.

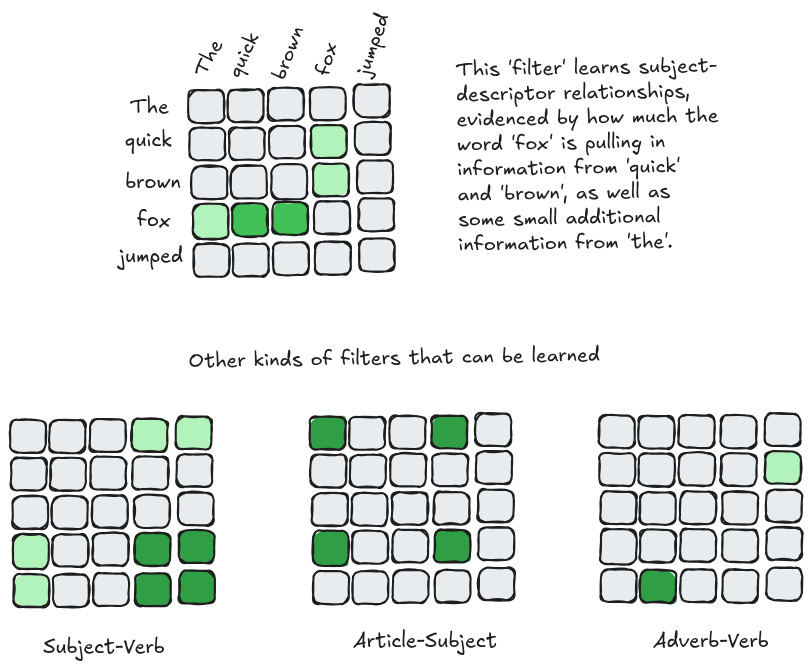

Of course, there are many paths to the Buddha. Another way to reason about transformers is to treat them as an abstracted convolutional network. In a normal computer vision task, you take an image that you can think of as a flat plane of numbers, and you slide another smaller window over the plane. Whenever the underlying input image and the window have a matching pattern you get a really high amount of signal, and whenever they have really disparate patterns you get a really low amount of signal. The 'window' ends up learning a specific aggregation, such as edge detectors or color differentiation. If you have many such windows, you can learn a lot of different patterns.

This is basically what a transformer does, but over sequences. The Query and Key linear projections each learn things like ‘this token is an adjective’ or ‘this token has many meanings’. These are then combined into attention heads that learn a specific convolutional filter over your input sequence. You can you can think of your input sequence as an image of sorts, where every 'pixel' in your image is a relationship between two nodes. And instead of sliding a smaller window around the ‘image’, your window (the attention matrix) is the same size as the underlying input. I call this the 'filter-centric' or 'operation-centric' view.

For me, both framings are useful because you can glean something about why these things work. In the former case, the transformer obviously has more representational capacity than a traditional RNN. In the latter, the transformer is strictly more general (or strictly less biased) than other architectures because it throws out any kind of human-derived heuristics and learns all relationships from scratch. As a result, I think transformers necessarily need a lot more data to really work — there is simply less ‘bias’ built into the model — but this also allows transformers to exceed other kinds of models in high data situations.

Of course, transformers do have that pesky quadratic compute problem…

Again, this paper is really an engineering paper, not a theory paper. The authors don't have a grand philosophy about why transformers are mathematically better than sliced bread. Rather, they care about mundane things like computational efficiency. The main problem being solved was the parallelization limitations of RNNs by moving away from sequential processing. And they weren't even the only people working on this problem. "Attention is All You Need" is merely the end state of years of research by dozens, if not hundreds of other scientists on the exact same problem.

Now that transformers have taken off, the pendulum has swung the other way: everyone is trying to figure out how to go back to linear, and potentially even serial compute.

The main transformer bottleneck is that the QK self attention matrix requires quadratic increases in memory and compute as a function of sequence length. Or, in English, each additional token in a sequence is exponentially more expensive than the last. This is why even now many top tier models are limited to ~100k context windows — it's simply too hard and too expensive to train models that can handle more.

So, the thinking goes, if you can create an architecture that can perform as well as transformers without having to pay the quadratic cost, you could seriously and dramatically expand how far a dollar of compute can take you. No one has quite cracked this, but there is a ton of research in this space including attention free transformers, state space models, linear attention, and even going back to regular RNNs. In the broader context, all of these papers are just the next iteration of the same compute efficiency conversation.

Cards on the table, I don't think any of those research efforts will meaningfully displace transformers, at least not for a while. Convolutional networks and LSTMs were originally formulated in 1989 and 1996 respectively. These were the common workhorse models for basically all deep learning tasks for a long time. It wasn't until 2014 that we got attention! It's possible that since there is so much focus on AI now, we'll see more breakthroughs in a shorter period of time. But we still have not made any real progress on formally describing deep learning, so in my opinion it's a bit of a crap shoot whether the next big architecture innovation comes next month or next decade.

My suspicion is that the bottleneck is, as always, compute. Transformers really shine when they scale up. We couldn't really implement a transformer in 2012 — the chips and data just weren't there. Since the release of AlexNet in 2012, our compute per GPU has gone up by a factor of ~3001 and we went from a million training samples (ImageNet) to trillions of tokens. So of course, transformers now work because we can manage their quadratic growth. I think any transformer successor won't really appear until we massively increase our compute and training data again. And more likely than not, it will be even more "inefficient" than transformers. Transformers scale quadratically with sequence length; their replacement may scale cubicly or even hyper-cubicly.2

In any case, for the near future transformers are here to stay. "Attention is All You Need" is currently sitting at ~200k citations. I think that number will keep climbing for a long while.

AlexNet was trained on 2 NVIDIA GTX 580s, each of which had 1.5 TFLOPs of compute. A single A100 has 624 TFLOPs of compute if you include sparsity optimizations.

idk if this is a word, but it seems right. The words "quadratic" and "cubic" both relate to geometric volumes, and a hyper cube is a 4 dimensional construct.