Agent orchestrators are bad

Everyone seems to be jumping on the agent swarm hype train. I think it's a waste of time.

Note: if you are interested in talking about AI agents with other likeminded operators, join the nori public slack! It’s a great place to share links and get feedback on how to best use agents.

I.

Agent orchestrators1 are popular and I don’t like them. If someone came to me and said “theahura, I have a great new product, it costs 100x more than what you currently do and produces worse outputs, do you want to buy it?” I would say something like “no.” I wouldn’t have to think very hard. Spending more for worse outcomes is usually the domain of enshitification, not innovation. But with good marketing, a fast moving industry, and enough FOMO, you can in fact put makeup on a pig. That’s basically what I think is happening with the current agent orchestrator craze.

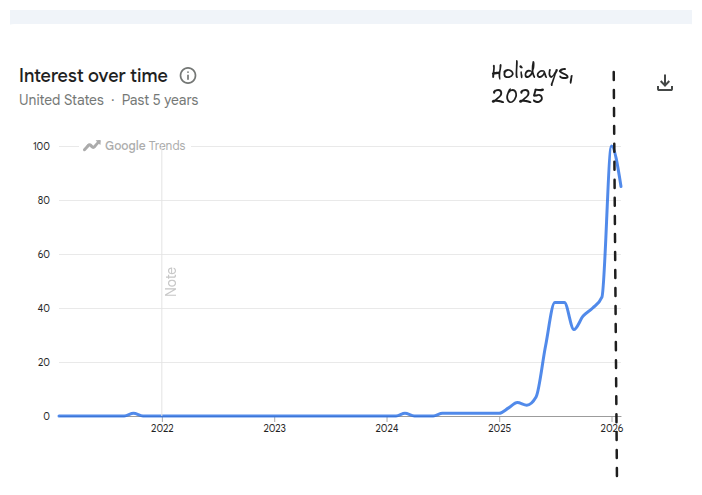

At a very high level, an agent is an LLM that runs in a loop. It takes in some user prompt and then uses a combination of its own outputs and available tools to follow up the original prompt. Agents really took off when everyone realized over the holidays that Claude Code is actually good.

Claude Code is a “coding agent”, an agent that is really good at reading files, writing files, and running code. I think coding agents are somewhat misnamed. Even though they were originally built to write code, it turns out writing code is equivalent to just operating a computer. So it’s often better/more informative to think of these things as general purpose.

An agent orchestrator is some system that can run many of these agents together. Often, the agent orchestrator is also itself an agent. This “orchestrator” agent can recursively create and spin off other ‘subagents’.

Over the last month, there has been a lot of hype around agent orchestrators. There’s ohmyclaude, an open source library that configures Claude Code to use its built in subagent library for every basic task. There’s crew.ai, which lets you create ‘teams’ of agents. There’s Claude Agent Teams. Google and Microsoft both have opensource agent experimentation frameworks. Cursor published that thing where they had a bunch of agents (try to) build a web browser. There’s Gas Town, which has quotes like this:

Gas Town is an industrialized coding factory manned by superintelligent robot chimps, and when they feel like it, they can wreck your shit in an instant. They will wreck the other chimps, the workstations, the customers. They’ll rip your face off if you aren’t already an experienced chimp-wrangler. So no. If you have any doubt whatsoever, then you can’t use it.

Working effectively in Gas Town involves committing to vibe coding. Work becomes fluid, an uncountable substance that you sling around freely, like slopping shiny fish into wooden barrels at the docks. Most work gets done; some work gets lost. Fish fall out of the barrel. Some escape back to sea, or get stepped on. More fish will come. The focus is throughput: creation and correction at the speed of thought.

And a million other projects on Twitter. People rightfully ask whether these platforms and techniques are any good. After all, there’s so much hype, so many GitHub stars. Surely this must be the magic sauce?

Unfortunately, no. Agent orchestrators aren’t good. I think there are some fundamental reasons why they may never be good, but they certainly aren’t good right now.

II.

Let’s start at first principles.

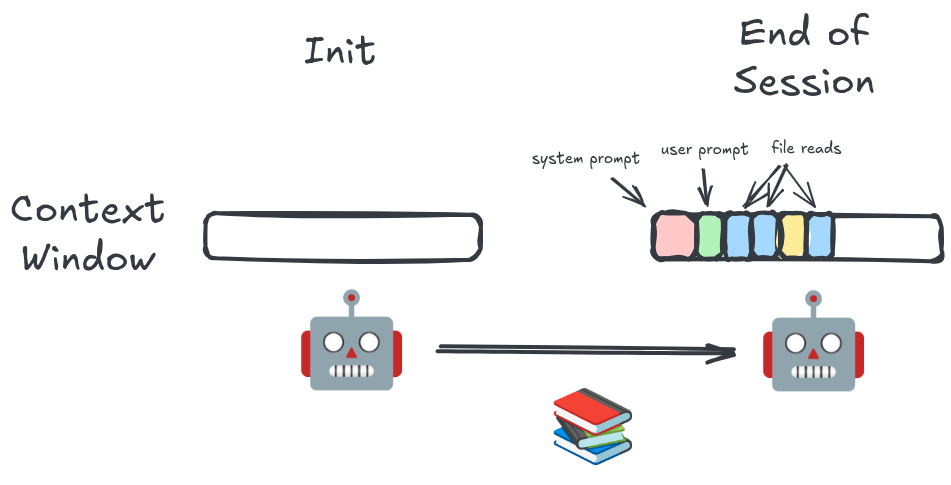

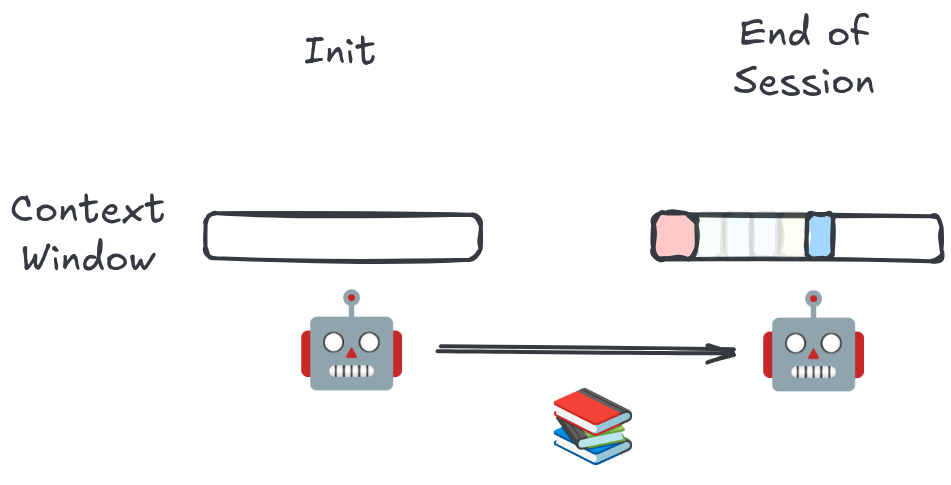

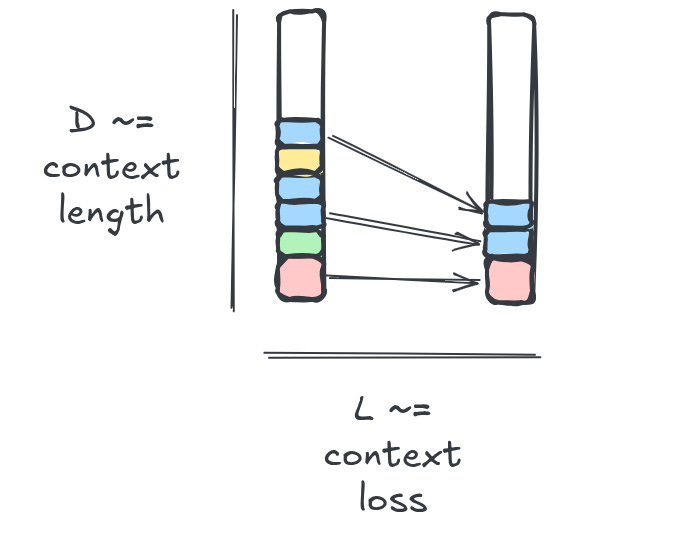

An LLM has a fixed amount of data it can process at a time. This is its context window and is denominated in tokens. Every single thing that an LLM “sees” is through the context window. That includes the system prompt, any user prompts, any agent responses, file reads, tool calls, etc. It’s all just tokens in the context window. Most LLMs have a context window of 200k tokens, though a few can go up to 1m. You can’t go past the context window. This means that your context window is a precious and limited resource, and a lot of working with agents is about managing this window.

LLMs will also get worse over time. When the LLM only has a few tokens in its context, it is better at answering questions and making good decisions. As a conversation goes on, the LLM will start to hallucinate and make mistakes. So in addition to the context window, there is an effective context window, past which it’s generally better to just restart the conversation. LLMs are known to pay the most attention to whatever happened at the very beginning of the conversation, and whatever the most recent message is. They lose the middle.

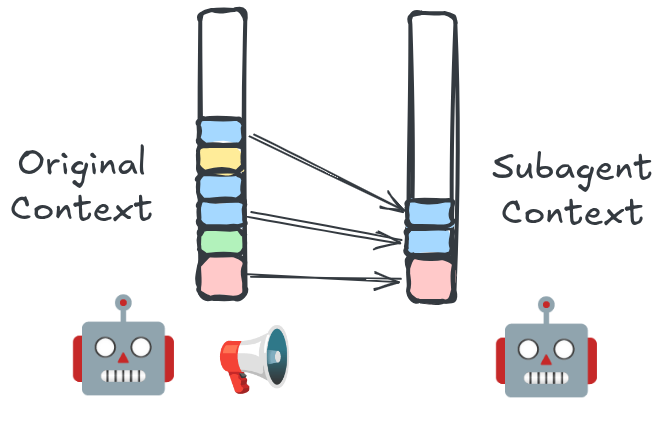

When an agent orchestrator spins up a subagent, the subagent has a completely different context window. The orchestrator generally decides what to put into the subagent. The orchestrator can only put some piece of its own context into the subagent.

So from here, we can pretty quickly derive the bull and bear case for agent orchestrators: they allow you to get past your context window limits, at the cost of some lossiness in what goes into the subagent context.

We can try to formalize the intuition here. There are two variables in front of us:

D, the degradation that models experience from long context;

And L, the cost of the loss of information across the gap between agents.

If L > D, subagents don’t make sense.

My hypothesis: for most tasks, L > D, and subagents do not make sense.

III.

There are a few reasons why this is true.

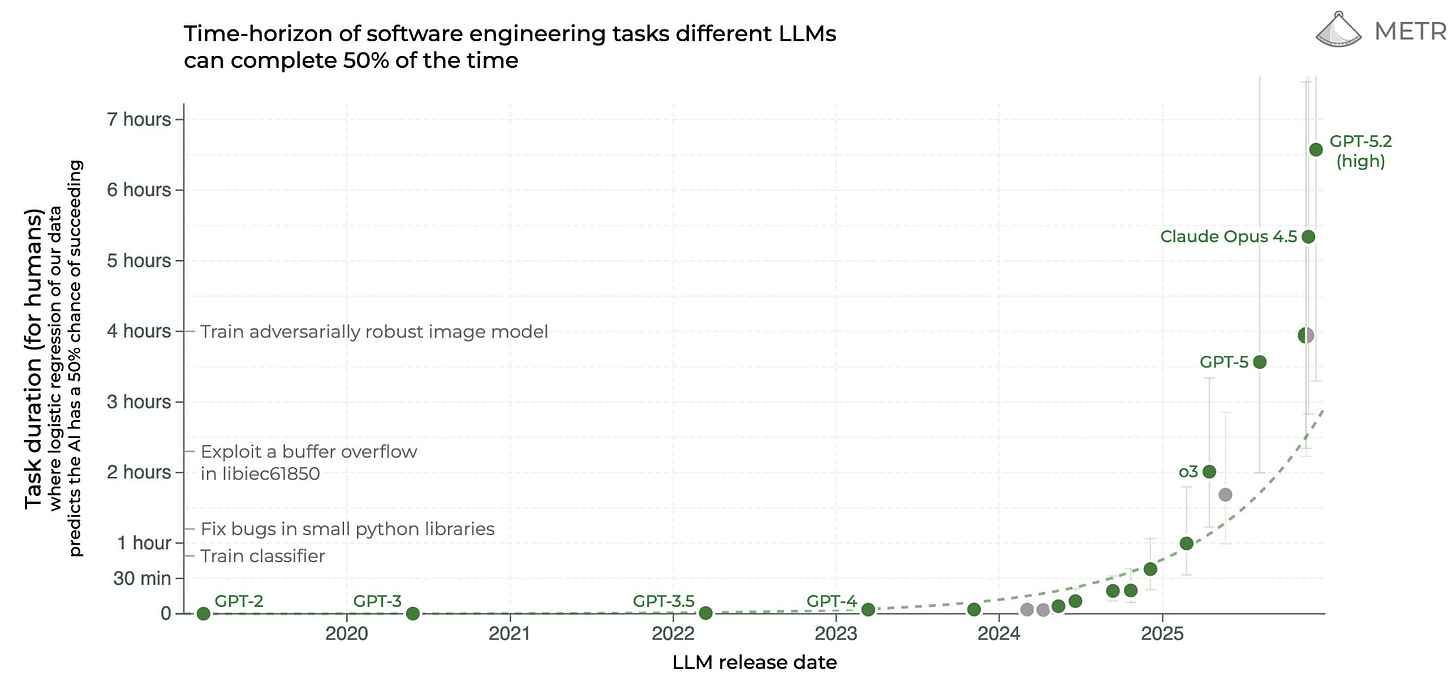

The big labs have spent a lot of time getting models to handle larger context. Context windows and effective context windows have steadily increased. Between memory files, config files, RAG systems, and docs, folks have built a lot of infrastructure to solve the context issue. Models are increasingly being trained on multi step tasks. As a result, the length of tasks that these agents can solve is increasing too.

So we have reason to believe that D, the cost of context, is steadily decreasing.

By contrast, there has been little to no training and far less infrastructure for models to message each other. And there is reason to believe that subagent lossiness increases exponentially the more agents there are in the chain.2 In other words, large subagent swarms are essentially a complex game of telephone. Agent 1 tells Agent 2 to fix a bug, and Agent 2 tells Agent 3 to remove the issue, and Agent 3 tells Agent 4 to remove the code, and Agent 4 tells Agent 5 to rm -rf the directory.

“But wait. We don’t need our agents to be in a big chain. A lot of tasks require parallelism, and subagent swarms can mostly work in parallel, all communicating with the same orchestrator. Doesn’t that offset things?”

We can try and fit this intuition into our formalization above. The cost of context, D, is basically the same regardless of what you ask the model to do, because it is dependent on the internals of the model. But the cost of information loss between agents is task specific. For some tasks, losing information between agents is really painful. For others, losing information may even be beneficial.

What kinds of things fall into the latter category? Some examples from my own work as a software eng.

Research. You open a bunch of tabs, search in each one, discard the ones you do not need, and summarize the results so that you can use them for whatever your main task is.

Debugging. You try a bunch of hypotheses to see where your bug is. One of them works. You throw away the rest.

File renames. Renames are very mechanical but may have a large surface area. You can parallelize them easily because each rename is independent from all of the others.

Review. Anything that requires a neutral evaluation of changes without looking at all the work in between.

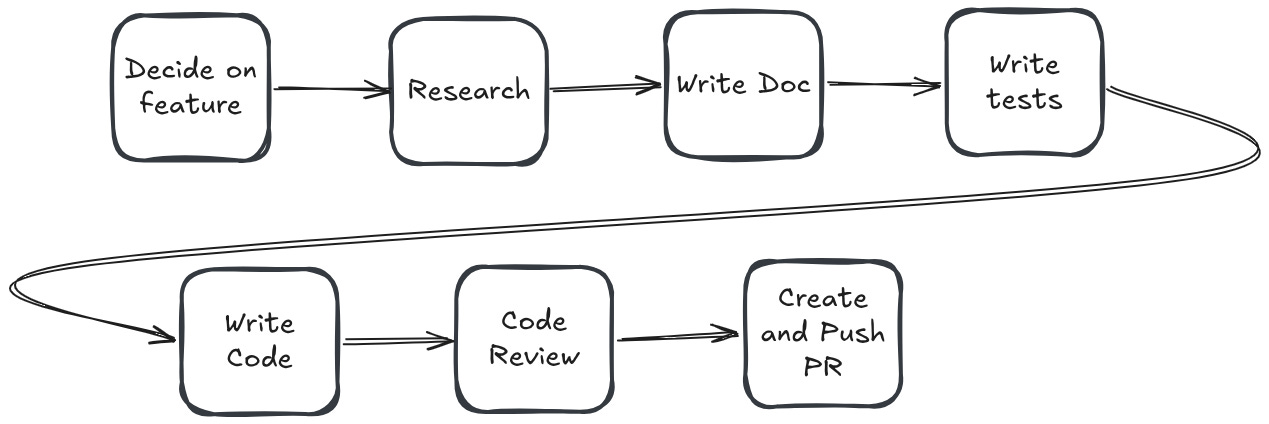

Building software mostly does not fall into this category. Think about the standard software flow. For me, it goes something like this:

Of course, I don’t actually do any of this myself. Besides the first step, I have an agent do all the rest. But note: it’s a single agent following my personal skillset, not a swarm. That’s because basically every part of this flow is highly dependent on the things that came before. You can’t write good tests if you don’t know what your implementation is! The cost of losing information over the course of the pipeline is extremely high. I think using agent swarms here is a great way to generate slop, because you are trying to fit a system for parallel lossy work into a sequential high-context workflow. For software engineering, L >>> D.

Interestingly, as this post was sitting in my drafts, Google released some empirical analysis3 that covers some of what I’m talking about here.

From the paper abstract:

We evaluate this across four benchmarks: Finance-Agent, BrowseComp-Plus, PlanCraft, and Workbench. With five canonical agent architectures (Single-Agent and four Multi-Agent Systems: Independent, Centralized, Decentralized, Hybrid), instantiated across three LLM families, we perform a controlled evaluation spanning 180 configurations…We identify three effects: (1) a tool-coordination trade-off: under fixed computational budgets, tool-heavy tasks suffer disproportionately from multi-agent overhead. (2) a capability saturation: coordination yields diminishing or negative returns once single-agent baselines exceed ~45%. (3) topology-dependent error amplification: independent agents amplify errors 17.2x, while centralized coordination contains this to 4.4x…For sequential reasoning tasks, every multi-agent variants degraded performance by 39-70%.

This matches my intuition. If you have a highly parallelizable task — like, say, renaming a bunch of files in a codebase and then updating all of the import paths — agent orchestration systems excel. But if you are doing something that is highly sequential, it all falls apart.4

IV.

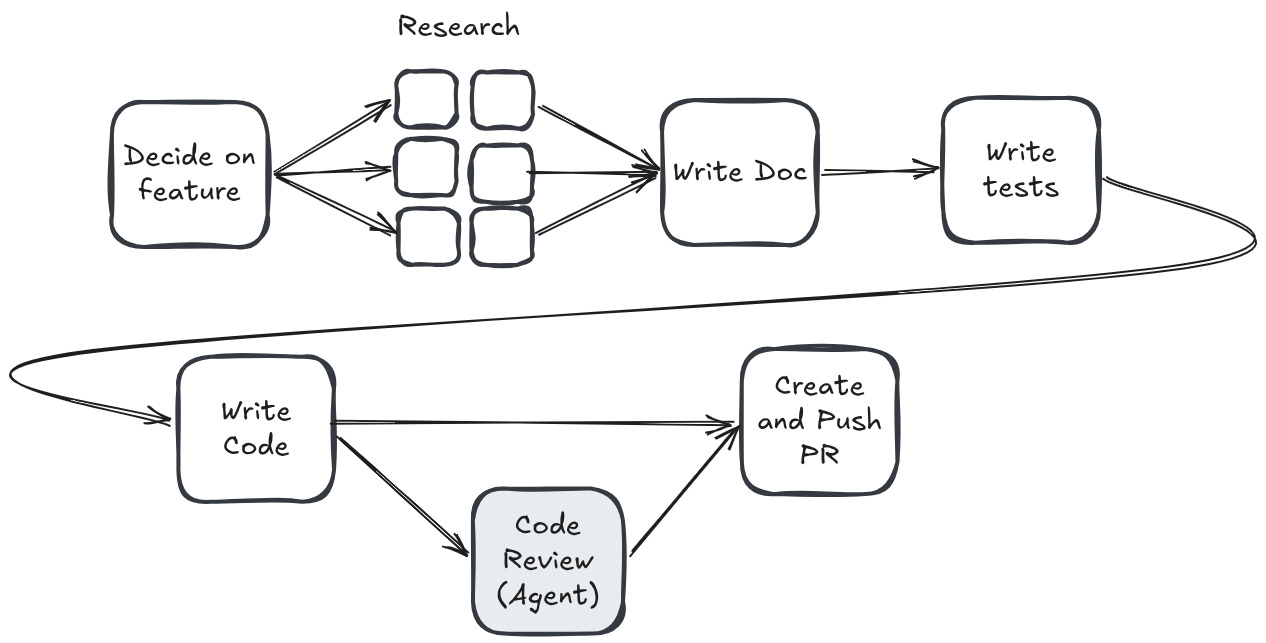

Ok but wait. I’m not being 100% honest above. There are places even within my own flow where I do in fact use agents. Subagents are way better at research, because you explicitly want to fan-out and discard. Code review requires ‘a fresh pair of eyes’ to be effective. So my workflow actually looks a bit more like this:

Does that mean that I am actually secretly using an agent orchestrator, and have been the whole time?

If you think of an agent orchestrator as ‘anything that uses subagents’, then sure, call me guilty. But I feel like there is an ocean between ‘a single task runner that carefully farms work out to subagents’ and whatever you call Gas Town.

GUPP is what keeps Gas Town moving. The biggest problem with Claude Code is it ends. The context window fills up, and it runs out of steam, and stops. GUPP is my solution to this problem.

GUPP states, simply: If there is work on your hook, YOU MUST RUN IT.

You can use Polecats without the Refinery and even without the Witness or Deacon. Just tell the Mayor to shut down the rig and sling work to the polecats with the message that they are to merge to main directly. Or the polecats can submit MRs and then the Mayor can merge them manually. It’s really up to you. The Refineries are useful if you have done a LOT of up-front specification work, and you have huge piles of Beads to churn through with long convoys.

In Gas Town, an agent is a Bead, an identity with a singleton global address. It has some slots, including a pointer to its Role Bead (which has priming information etc. for that role), its mail inbox (all Beads), its Hook (also a Bead, used for GUPP), and some administrative stuff like orchestration state (labels and notes). The history of everything that agent has done is captured in Git, and in Beads.

So what is a Hook? Every Gas Town worker has its own hook 🪝. It’s a special pinned bead, just for that agent, and it’s where you hang molecules, which are Gas Town workflows.

“Idle polecats” is an example of a heresy that plagues Gas Town. There is no such thing as an idle polecat; it’s not a pool, and they vanish when their work is done. But polecats do have long-term identities, so it’s more like they are clocking out and leaving the building between jobs, which is harder for agents to wrap their heads around. So “idle polecats” make it back into the code base, comments, and docs all the time.

I think it is really critical to tease out exactly what the distinction is. Agent orchestrators like Oh My Claude or Gas Town treat agent swarms as general purpose hammers instead of task specific scalpels. They want you to use swarms for everything.

But this begs the question: what do you actually get from doing this? The actual interface to the end user is the same. The user should not know or care how many agents sit behind the chat window. And as I said above, I really do not think that the agent orchestrators result in better outputs. So why the hype?

Three thoughts.

I’ve been writing about my startup nori on and off on this blog since December (soft plug: if you / your team is struggling to adopt AI agents, we can help! Drop us a line). One of the core insights of our sales motion is that there is a ton of FOMO right now. Everyone is feeling it. Even engineers that are literally at the cutting edge are looking over their shoulder and feeling FOMO. And when the market feels FOMO that intensely, it starts reaching for anyone and anything that may resolve it. I can practically see the thought process. “Agents don’t work for me, I must be doing something wrong…maybe I need to use agent swarms!” It’s snake oil logic. And it results in castles built on sand that come crashing down.

Agent orchestrators may also be tempting because they mimic how work happened in the old world. You would have specialization — engineers and QA folks and PMs and marketers and sales people. It’s hard to reason about what coding agents can do; much easier to structure an ‘agent team’ that is composed of ‘specialists’ who can all hand off work between each other. Sure, it is 1000x the token cost, but it feels right, because it feels familiar.

But the main reason for the hype is because it feels productive to tinker with agent orchestrators. There was a fantastic article that was making the rounds a few days ago, about LLMs as tool-shaped-objects. Quoting liberally:

I want to talk about a category of object that is shaped like a tool, but distinctly isn’t one. You can hold it. You can use it. It fits in the hand the way a tool should. It produces the feeling of work-- the friction, the labor, the sense of forward motion-- but it doesn’t produce work. The object is not broken, it is performing its function. It’s function is to feel like a tool.

A woodworker who spends six figures a year on exotic hardwoods he will never build with is not investing in output. He is investing in scrap. The wood exists so that the tools have something to touch. The shavings and scraps are the product.

The current generation of LLM-driven insanity — the billion dollar frameworks, the orchestration layers, the agentic workflows— is the most sophisticated tool-shaped object ever created.

What makes this particularly difficult to see is that LLMs are also, genuinely, tools. They do real work. The line between the tool and the tool-shaped object is not a line at all but a gradient, and the gradient shifts with every use case, every user, every prompt. You can only fail to notice when you have crossed from one side to the other.

Agent orchestrators are tool-shaped-objects. You can spend endless amounts of time configuring your agent harness, and you end up with something that spends more money for worse output. But it feels like you are making progress, and that is enough to give virality.

V.

It seems obvious to me that agent orchestrators will eventually become useful. Teams at Cursor, Anthropic, Google, OpenAI, and Ramp are all experimenting with agent swarms.

Still, as far as I can tell, agent swarms are not yet being regularly deployed on any product surfaces, despite the fact that those products are increasingly being written by AI. That’s because AI can’t yet build product. The companies above are building research projects in really well specified areas, or generic frameworks without any claim about efficacy. The C compiler is a great example: it’s hard to build, but is really well specified. Not at all like a potentially-easy-to-build product that needs to land at the right time, with the right execution. More generally, it seems to me like most of the folks who are buzzing about multi-agent collaboration are researchers. Which makes sense, because this is an active area of research.

I keep coming back to this question: ‘what are the agent swarms for?’ For me, agentic work is about saving time. I want to be able to throw increasingly vague requests at my agents and get increasingly high quality responses. I want agents that can ingest all of the context about my company and use that context to implement extremely abstract requests. I want to pull myself out of the loop wherever possible.

That does not require more hands. It requires analysis about where the company is situated in the market, how the product currently functions, and what is the next most important thing to build. This is why I am always skeptical when people say that they can just ralph wiggum loop whole products. You can write specs for anything. Is it worth writing a 20 page spec treatment on social media for pet owners? And if you just mean that you can build software faster now, well, yea, join the club. You don’t need agent swarms to do that. If anything, the agent swarms are slowing you down and draining your bank account.

In my mind, the best application for agent orchestrators is ‘solving’ context rot. If agent swarms get good enough that they can handle extremely long running tasks, great, amazing. I want that, because I want to intervene less. But in that hypothetical future, the agent swarms will be interfacing with the user as if they were one coherent agent. It’s a band-aid for not having larger models.

And it is, still, a hypothetical future. In the current implementation, they mostly make context rot worse. They don’t save my time. And so I can’t recommend using them until they improve.

Also: agent swarms, subagents. I use these all interchangeably

Quick intuition pump: if there are B bits of information that need to be transferred, and there is X% likelihood that any given bit does not get transferred, then for a chain of N subagents you’d multiply X% * X% * X% … N times.

Paper linked here: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.08296

The authors of the paper used a few benchmarks: PlanCraft, a Minecraft benchmark with rigid sequential constraints; Finance-Agent, a financial reasoning benchmark with naturally decomposable subtasks; BrowseComp-Plus, a benchmark about information retrieval; and Workbench, a benchmark of common workplace tasks that involve a lot of tool calls. Of these, PlanCraft is the only one that has strict sequential dependencies.

Good post! I agree with a lot of this, and I say that as somebody who lit money on fire trying gastown just in case Steve was right. But I think we're going to see functional agent swarms a lot sooner based on the RLM architecture. Agents calling other agents programmatically and passing them variables gets around the issue of all I/O having to go through the mode'ls context window