Tech Things: OpenAI's Magic Money

Investments in private companies can be dangerous for your health

One of the things that you learn when you’re in the startup world for any amount of time is that paper valuations and real valuations are two very different things. For example, imagine I have a company with 1 million shares, and the only thing I have related to that company is a slide deck and a winning smile. Say I sit one of my friends down and pitch him on the company. And say he’s excited to invest — he wants to buy one share for $10. I say great! and hand him a contract that he signs. Here’s a question: is my company now worth $10 million dollars? I think, instinctively, most people would say no.

But say I have a company with 1 million shares, and I go with my slide deck and winning smile to a16z. And after pitching them on the company, they agree to buy 100000 of those shares (10%) for 1 million dollars. Now is my company worth $10 million dollars? Actually, kinda, yes. Even though from an accounting perspective, nothing has really changed and in both cases all you have is a slide deck and a winning smile.

Private companies are these weird, opaque parts of the market. They don’t really trade regularly, so you don’t ever have an accurate idea of what the company is worth. The best you can say is that you know what one person thought it was worth when they last purchased shares, and even that is fuzzy. Sometimes, 10% of a company is only worth $1M if the current founders own the other 90%. This is why you must be an “accredited investor” to even try and invest in private companies. When accredited investors invest, they are more or less on their own. So in theory, there’s an expectation that they will diligence the company to make sure they aren’t buying snake oil.

In practice, what, are you kidding? Even in normal conditions, you can tell a pretty convincing story to investors without having anything real at all and still get a massive amount of money. Especially if you can create hype, and especially especially if you can get into a bidding war. Matt Levine had a great take about this re. Mira Murati’s startup Thinking Machines:

In theory there is an incredible arbitrage here. If you are a top AI researcher, probably a lot of your friends are also top AI researchers. If you all got together, you could (1) hang out and have fun and (2) also do some top AI research. And then you could go out to investors and say “hey, look, top AI researchers here, give us a billion dollars.” And if the investors said “yes but what are you all doing together,” you could give them a disapproving look and take a step toward the door, and they would say “we’re so sorry, we don’t know what we were thinking, to make it up to you here’s $2 billion.”

And then you’d have $2 billion dollars to hang out with your friends. And do top AI research with them, if you want. You probably do want! That’s how you got to be top AI researchers. But do you need to do boring stuff like have a business plan or pursue revenue? I don’t … I don’t really see why you would?

…

At the Information, Stephanie Palazzolo has an incredible article about Mira Murati’s AI startup:

Not only has the one-year-old Thinking Machines not yet released a product, it hasn’t talked publicly about what that product will be. Even some of the company’s investors don’t have a very good idea of what it is working on. While raising capital for Thinking Machines earlier this year and late last year, Murati shared few details about what it would be building, prospective investors said.

“It was the most absurd pitch meeting,” one investor who met with Murati said. “She was like, ‘So we’re doing an AI company with the best AI people, but we can’t answer any questions.’”

Despite that vagueness, Murati raised $2 billion in funding—the largest seed round ever—at a $10 billion pre-investment valuation from top Silicon Valley VC firms including Andreessen Horowitz, Accel and GV. The investors also made the highly unusual decision to give her total veto power over the board of directors.

I’m sorry but that’s the best pitch ever! That is the platonic ideal of a tech startup pitch! Murati and her employees are extremely valuable, and they monetized that value directly. Why should they have to build a product?

Murati’s company has since started actually putting out work, and some of that research is legitimately interesting and important. But the broader point stands: there are many many startups that on paper are worth millions or even billions (based on the last funding round) but in practice are worth approximately the value of their domain name.

Now, there’s an obvious gradient in how ‘real’ a private company’s valuation is. No matter how much funny accounting I do, the company that I started last week is way less valuable than, say, OpenAI stock, in real terms. I can’t quite buy a hot dog with OpenAI stock, but there are ways I could turn that stock to money and then use the money to buy a hot dog. I can’t do that at all with my fictional company’s stock. But I mention all of this because there’s a lot of gray area even in the OpenAI side of the market. Paper valuations are rarely what they seem, and the bigger the private company the more opportunity there is for shenanigans.

Like these:

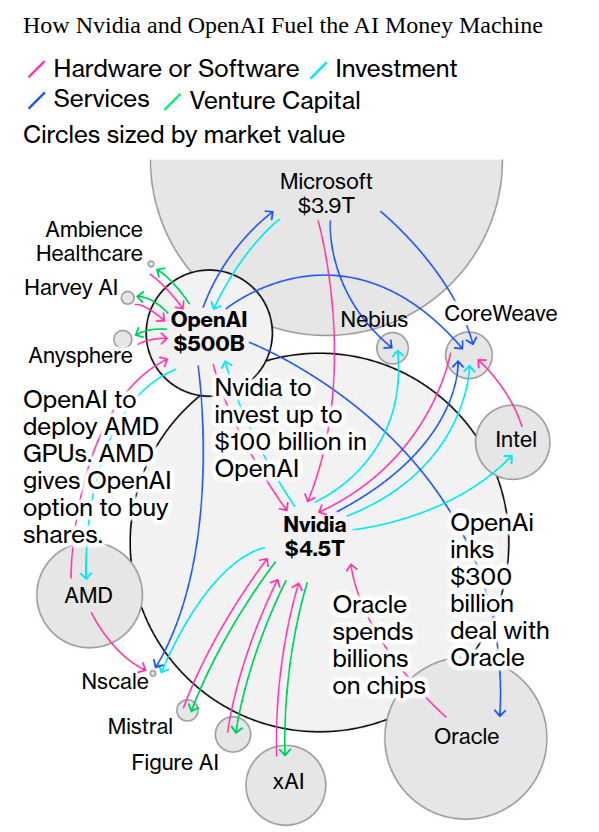

Two weeks ago, Nvidia Corp. agreed to invest as much as $100 billion in OpenAI to help the leading AI startup fund a data-center buildout so massive it could power a major city. OpenAI in turn committed to filling those sites with millions of Nvidia chips. The arrangement was promptly criticized for its “circular” nature.

This week, undeterred, OpenAI struck a similar deal. The ChatGPT maker on Monday inked a partnership with Nvidia rival Advanced Micro Devices Inc. to deploy tens of billions of dollars worth of its chips. As part of the tie-up, OpenAI is poised to become one of AMD’s largest shareholders.

…

The day after Nvidia and OpenAI announced their $100 billion investment agreement, OpenAI confirmed it had struck a separate $300 billion deal with Oracle to build out data centers in the US. Oracle, in turn, is spending billions on Nvidia chips for those facilities, sending money back to Nvidia, a company that is emerging as one of OpenAI’s most prominent backers.

That’s all from an article by Bloomberg, which also had this fantastic image:

They go on to say:

Some analysts and academics who’ve tracked the tech industry long enough see uncomfortable similarities to the dot-com bubble. “In the late 1990s, circular deals were often centered on advertising and cross-selling between startups, where companies bought each other’s services to inflate perceived growth,” said Paulo Carvao, a senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School who researches AI policy and who worked in tech in the late 1990s. “Today’s AI firms have tangible products and customers, but their spending is still outpacing monetization.”

Here’s a little magic trick. NVIDIA announces a deal with OpenAI. NVIDIA “invests” $100b into OpenAI. So OpenAI is now ‘worth’ $100b more. But OpenAI turns around and gives that money right back in the form of buying GPUs from NVIDIA. So now NVIDIA gets to say that they are ‘worth’ $100b more too! Somehow, $200b in paper value was added to the market because NVIDIA gave OpenAI GPUs for free.

Well, not actually for free. Depending on the terms of the deal, NVIDIA got something for its initial investment in the GPU build out. Traditionally, when you invest in a private company, you get that company’s stock. Like we said above, the stock has some nominal value — whatever value you bought it for, to be precise. But in a real sense, it has no “hot dog” value; you still cannot buy a hot dog with it. So we’re right back in that fuzzy world of private valuations. OpenAI is collateralizing all of this with their own stock, which is basically worth some made up number, and that made up number is being determined by…the people who are getting big stock price boosts for standing next to OpenAI! The made up OpenAI prices are boosting the real NVIDIA prices, which is then used to further boost the made up OpenAI prices!

So one way you could read all of this is that money is pouring in through NVIDIA and AMD and all of these other places, and it’s going to OpenAI, and in return, OpenAI is just giving back bigger and bigger IOUs to the people investing in NVIDIA and AMD. You might think you’re buying NVIDIA stock, but actually you’re buying OpenAI IOUs. That house of cards is currently worth $500 billion dollars but only on paper.

I’m not the first person to say that the entire US economy seems structured around datacenter capex right now. Thanks to the disastrous policies of this administration, everything else has slowed to a crawl. So all of this raises a really important question, and maybe the only question that matters to the global financial system: is that $500 billion sticker price accurate?

About a month back, there was a blog post that made it to the top of hackernews, where one Martin Alderson did some back of the envolop calculations on whether or not OpenAI was making money using some estimates of their GPU-cost-per-hour. It’s a great post, and he came up with some very bullish numbers:

Current API pricing: $3/15 per million tokens vs ~$0.01/3 actual costs

Margins: 80-95%+ gross margins

The API business is essentially a money printer. The gross margins here are software-like, not infrastructure-like…Even if you assume we’re off by a factor of 3, the economics still look highly profitable. The raw compute costs, even at retail H100 pricing, suggest that AI inference isn’t the unsustainable money pit that many claim it to be.

The key insight that most people miss is just how dramatically cheaper input processing is compared to output generation. We’re talking about a thousand-fold cost difference - input tokens at roughly $0.005 per million versus output tokens at $3+ per million.

This cost asymmetry explains why certain use cases are incredibly profitable while others might struggle. Heavy readers - applications that consume massive amounts of context but generate minimal output - operate in an almost free tier for compute costs. Conversational agents, coding assistants processing entire codebases, document analysis tools, and research applications all benefit enormously from this dynamic.

Unfortunately, even though he makes reasonable estimates, I end up disagreeing with his conclusions.

The problem is that Martin did not account for the cost of training these models. [EDIT: I'm wrong about all this math, see JV in the comments. Tldr, I need to divide the training cost across all compute clusters, not just the one that Martin did the calculations for] He only looked at inference. You need to amortize the cost of the training over the lifetime of the model. The most recent OpenAI model to finish a product lifecycle was GPT4. There were 21048 hours between when GPT4 was released (in March 2023) and when GPT 5 was released (August 2025). I don’t have an immediate gut sense of how much GPT4 cost to train, because there are so many random estimates floating around. Say GPT4 cost as much as DeepSeek to train, i.e. $5m. That means you would add an additional $230 per hour to the cost of running GPT4 inference. So the total would be ~$380 per hour, or roughly 3x the costs that Martin lays out. As Martin states, that is still extremely profitable. But say GPT4 cost as much as Sam Altman says it did, i.e. $100 million. Now you’re adding ~$4750 per hour to the cost of inference, or roughly 33x the costs that Martin lays out, not including salaries. Suddenly things are looking way less profitable for OpenAI.

I’ve heard rumors that OpenAI is planning to IPO, in which case suddenly all that stock would be worth some very real number. It remains to be seen whether it will be anywhere close to $500 billion. But if it’s not — or if investors realize that the god-in-a-box that Altman keeps promising isn’t right around the corner and decide to pull out of the bubble — we’re going to be in bad shape for a while.

I'd add that there's another way to create magic money, which is long term contracts.

Let's take the $300B contract between Oracle and OpenAI as an example, a "5 year deal for $300 million," which starts in 2027. It's a nice win for Oracle, they can have a splashy announcement and list that as remaining performance obligations.

That's much better for Oracle than just building the data centers and making money afterwards. That approach would show up as cost during construction, and then in annual revenue. And meanwhile Oracle gets a brand boost where they claim to be a leader in AI. And for that privilege they may even make it easier for OpenAI to get out of the deal.

Now, RPOs have value, but they are also another way to inflate numbers in order to impress investors and the public.

"That means you would add an additional $230 per hour to the cost of running GPT4 inference. So the total would be ~$380 per hour, or roughly 3x the costs that Martin lays out."

You are adding the total training cost to the cost to operate a single inference cluster. Based on recent numbers OpenAI inference fleet is equivalent to thousands of such clusters. (Epoch said 480k H100 in their digital worker estimate.)

Even if the training cost was $100M and only 1000 clusters were running GPT4 for its lifetime of 20k hours, that adds just $5 per hour to costs.