Coding agents suck at microservices

Somewhat contra humanlayer on docs

If you work with coding agents, you know that managing context is critical. Coding agents — and really all LLMs — have a limited context window with which they can do things. There is a hard cap of how much information you can shove into the LLM. And each additional token you throw in there results in the model performing worse. This is known as ‘context rot’, and it is the number one reason why people have bad experiences with these models. In order to get LLMs to work, you need to be really cognizant of what data you are putting into your context window. This requires being very discerning about what content is ‘relevant’ and what is just noise.

This is a search problem.

Very broadly, you can define a search problem as any problem where you have to figure out which documents are most relevant for a specific query. Search is a hard problem. Part of the reason it is hard is because it is ill-formed. What does ‘relevant’ even mean? People have spent a lot of time and energy coming up with decent definitions of measuring ‘relevance’, from page-rank (the most relevant documents are the ones that have the most backlinks to them) to keyword search (the most relevant documents are the ones that exact or fuzzy match the query) to semantic search (the most relevant documents are the ones that have similar neural network embeddings). Giving coding agents access to powerful search is really important. This is why so much effort has been put into RAG, and why Anthropic makes Grep its own independent tool, and why there are so many startups that are essentially some variant of using turbopuffer to host some kind of data for agentic uses.

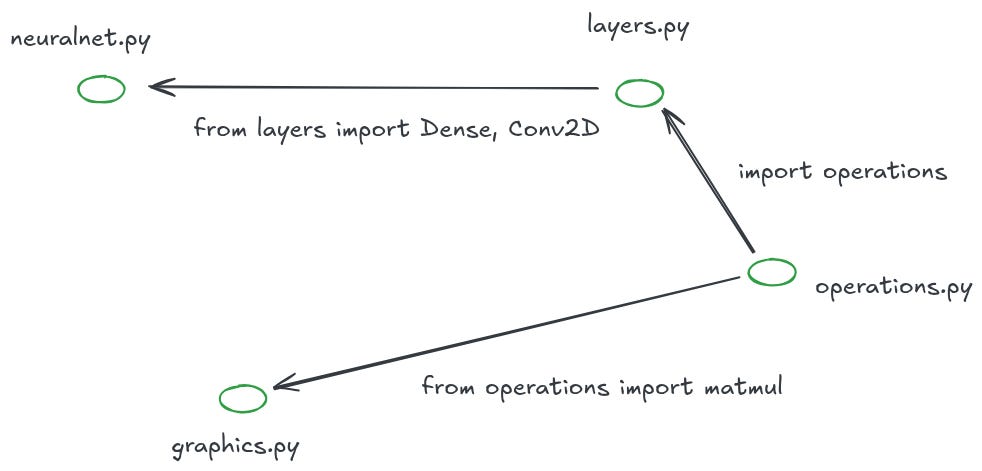

There is one thing that makes the search problem easier when programming: all code is a graph.

When you are writing code, you have to construct discrete links between files and functions for the compiler to actually process them. As a nice side effect, you can then use those links to drop into any part of the codebase and quickly pull in relevant context from other files, even if those files are really far away in the code tree. If you’ve ever used a ‘lookup this function’ or ‘lookup this variable’ tool in an IDE, you’ll know what I’m talking about.

The key innovation behind page rank was recognizing that links to a document are a fantastic measure of relevance. The same is true in code. In order to understand a given file, look at the files it imports!

Coding agents are really good at following these graph structures. Claude Code will look at a file, grep for symbols or follow import paths, and pull in the surrounding context. The graph acts as a path for the model to follow, ensuring that it only keeps relevant data in its context.

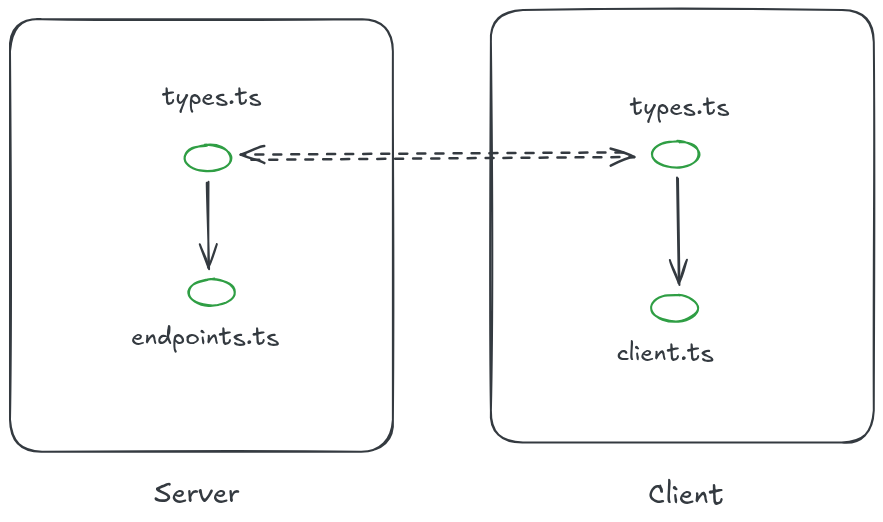

Here’s a really common architecture that is a bit of an anti-pattern.

You have some endpoints file that lives on a server and some client for that server. The client and the endpoint share the same types. But the types themselves are duplicated. There is no direct connection between the types that are imported by the server endpoints file and the types that are imported by the client handlers. Most of the time, the types are kept in sync by hand — the developer is responsible for making sure that the two files align. This is an invariant, something that is true (or must be true) about the program for it to work, but is not inherently enforced by the program itself.

Why would you create invariants like this one? For the same reason we have APIs and protocols and libraries and package managers: modularity. If I build a tool that calls out to the Stripe API, I do not have to worry about how that API is implemented. I can just assume that their docs are correct and treat their services as a black box. The same logic applies to internal codebases. This is, of course, the core principle behind microservice architectures. Each microservice does one thing really well, and services communicate with each other through clean boundaries and APIs, and each service ideally does not change very much, if ever, because the service does only one reasonably small and contained thing.

The problem with services architectures is that each API call is a hidden dependency, undocumented by the code itself. When you call service A from service B, you implicitly assume that B has knowledge of A’s endpoints — what endpoints exist, what parameters are required to use them, etc. That assumption may be wrong! Maybe service A changed its endpoints in the last three days and now everything that service B does is going to error. There are a lot of tools that help avoid this. GraphQL is the big one. Also various API builders that turn rest endpoints into client libraries automatically. But setting these up is hard and rarely worth it for smaller teams.

Back to coding agents. A proof in four parts:

It’s important to manage the context for a coding agent.

Coding agents can use the code graph to figure out relevant context automatically.

Service architectures break the code graph, creating hidden dependencies.

Therefore, coding agents will be bad at operating in services-heavy codebases.

QED.

Anecdotally, many people report that coding agents perform better in monorepos and monolith architectures. Based on how coding agents get context, this is totally unsurprising.

There is one way around this: docs.

I think recently there’s been some push back against docs, especially for coding agent use cases. The main reason is that docs can easily fall out of date. It’s a valid concern. But also massively outweighed by the benefits. Docs are the only way to express intent in code. They explain why the code exists and can express paths that were attempted but deemed unworkable. And most importantly, docs fix your graph. Good docs files will reference explicit file paths and capture invariants in your code. These act as additional sources of edges between nodes, breadcrumbs that your coding agents can follow.

Also, bluntly, I have never actually experienced an issue with docs being out of date since we started having the AI write our docs. Nori agents are required to read and update docs files any time they want to make a change to a folder, and it works great! We see huge lift from having docs.md files, even when we also have things like subagents trawling through code. These things go hand in hand — the former can drive the latter, the latter can correct the former.

This is at least partially a response to Dex from Humanlayer and his most recent talk at AIE:

It’s a fantastic talk and I agree with a lot of it. But I pretty strongly disagree that you should get rid of docs and instead only look at the code as ‘ground truth’ with subagents. Code is high precision, low recall. Every single thing that is in the code is true, but it is an incomplete story, and there is a lot of stuff that you will never glean from the code alone. IMO bad docs that convey some signal and some noise are better than no docs at all, because the kind of signal they convey is fundamentally different. This is true for humans, and I think it is true for coding agents as well.

If you’re interested in coding agents, you should download Nori! It has up to date configs for getting the most juice out of Claude Code. And you can read more about how I think about coding agents below: