Averaging 10+ PRs a day with Claude Code

If you use Claude Code, try nori-ai, it's really good

If you want to also be a Claude Code wizard, you can download all of my configs and embedded expertise at github or npm. It is easy to set up with a single command — npx nori-ai@latest install. If you are part of a larger team, reach out directly at amol@tilework.tech.

I guess I’m what you would call an early adopter to the coding agent thing. I started programming primarily with LLMs in August of last year. When I tried cursor, I thought “wow, this may be the first IDE to get me off vim.” It wasn’t. Within a week, I got tired of how long it took to open. It’s a text editor, why is my laptop fan screaming like I just opened Autodesk?

But I saw the potential.

I found a package that let me do everything I wanted to do with cursor in neovim. So I learned a bit of lua and updated all my configs and I haven’t looked back since. I think it’s been a year since I last wrote a full pr, end to end. Sure I’ll add a few tweaks here and here, but I’m basically never actually writing code anymore. I’ve iterated a few times, from in-file coding assistants to in-terminal coding agents. Today, my usual workflow looks something like this:

Get into the office around 1030AM

Spin up ~5 terminal panes in tmux running Claude Code (I can rarely parallelize more than that)

Look at my to-do list of small phrases and notes that remind me of things I need to build

Flesh out the task descriptions and farm them out to each Claude Code agent

Round robin between panes as each one needs my attention

Do code review as each Claude Code agent finishes its tasks and submits PRs

Add new tasks to the Claude Code agents as needed

I’m averaging ten or so PRs a day. One day this month I hit > 25. Are these all, like, Google standard PRs? No, of course not. But they are all tested, documented, and represent actual features/bugfixes/improvements being deployed to customers. Mostly not slop (and the ones that are slop don’t get merged).

I think people underestimate how much configuration is required to get to this point. I really spent a lot of time tweaking and dialing every setting until it all worked. It’s hard to expect everyone to do that. Most of us have day jobs that don’t involve reading all of the documentation that Anthropic puts out. So I figured I would share some ideas and principles that have worked for me, in the hopes that other people find it valuable.

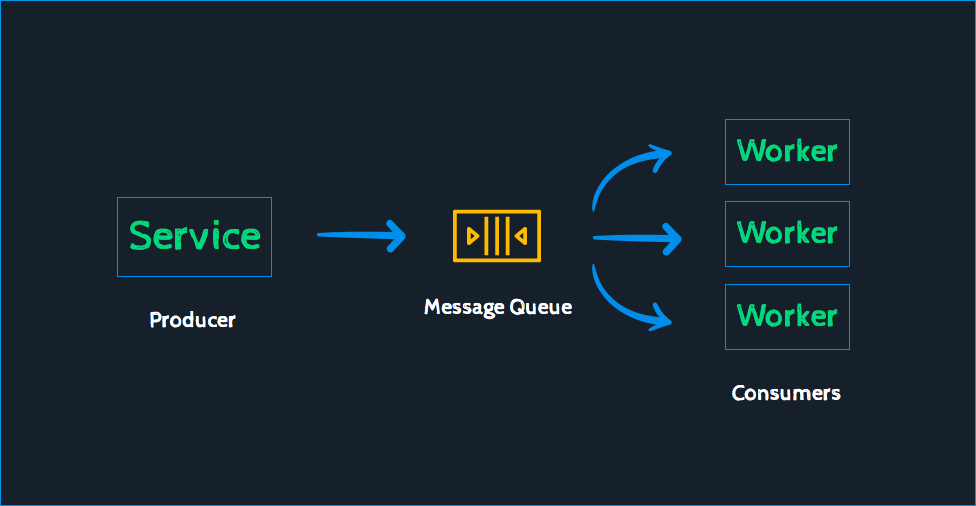

Your workflow is a distributed network. Parallelize aggressively.

When working with coding agents, I think of myself as part of a distributed network. I have a queue of tasks. I have a pool of Claude Code ‘worker threads’ that are cheap and easy to spin up. And I have a single, very expensive orchestrator that is a bottleneck for everything else: me.

This is essentially identical to an async web server that has to manage long running tasks. The main thread can kick whatever it wants to the back of the event loop. And it is critical that the main thread never gets blocked so that the server remains responsive. Similarly, I am the most important resource in the network. It is critical to keep my thread as unblocked as possible.

Claude Code sessions are basically free. Their output is very cheap. I can keep them running, and eventually they will spit something out, and I can easily throw whatever it spit out away at ~0 cost. The bottleneck for how many features I can get through is how many tasks I can accurately convey to the agent pool, and how often the agent pool is waiting to ask me things.

I keep myself unblocked by:

Enforcing git worktree usage. If I am running a single Claude Code agent, my time is just wasted while I am watching Claude write code. Worktrees let me run multiple agents in the same local repo.

Adding notification hooks to alert me visually. Any time any Claude agent is idling, I want to know so I can tab over and see what it needs.

Investing heavily in up-front research and planning. A single bad line of code is easy to fix. A bad spec or plan means throwing out an entire thread’s worth of work. Generally, if I approve a plan, the code is much easier to approve during code review later on.

Use coding agents for non coding tasks. Most often, search (as in, “come up with a few ideas of how to solve this problem”)

Test driven development

Agents have context rot. Over a long conversation, their performance and memory will degrade. If you can formalize what they need to accomplish at the very beginning, they will perform much better over longer conversations because they have a point of reference.

Test Driven Development is a coding paradigm that focuses on using tests to create concise, maintainable code. The core idea is to write tests to validate behavior before writing any implementation. If the tests are good, you can more or less write the code on autopilot — instead of trying to build in complicated behavior, your goal becomes “make the test pass”. Which is, of course, much simpler.

Hopefully you can fill in the gaps.

I make my coding agents follow test driven development. Any time they do anything, they have to write a test first. This has been critical for massively increasing my effective context window. With TDD, my coding agents are able to effectively one-shot significantly more ambitious problems, and I am consistently surprised at what they can tackle.

Also, writing tests has the added benefit of putting safety rails around future changes! You can think of testing as a formalized way of telling your coding agent what context is important — if something breaks, Claude knows that it has to go look at whatever broke! So TDD is a double whammy. It makes Claude better per session, and it makes Claude safer across sessions.

Documentation

Agents do not learn across sessions. This leads to a surprising amount of cognitive dissonance, and I personally think much of the frustration with using coding agents comes from not fully grappling with how alien these things actually are. Even though I know better, I often find myself explaining things to the coding agent as if it will remember the lesson for later. It does not, because natively it cannot.

Luckily, we can pull a memento and leave sticky notes everywhere.

Coding agents get significantly better at one-shotting problems when they have the ability to pull in relevant context. That means the context has to actually be present, either in the code base or accessible through tools. The most important context is, funny enough, previous transcripts between the engineer and the coding agent.

If data is the new oil, then the transcript between an engineer and a coding agent is premium grade gasoline. I’ve argued in the past that code is not the most important part of programming. Programming is an act of problem solving; the code is merely an artifact.

The word “programming” has a fascinating etymology. It derives from the word ‘program’, which in the 19th century meant ‘a plan or scheme announced beforehand’ and in the 17th century meant ‘written notice’. That in turn derived from programma (Latin) and prographein (Greek), meaning ‘to write publicly’.

I’ve recently been thinking about Theory-building and why employee churn is lethal to software companies, a blog post from one Baldur Bjarnason. To paraphrase slightly, the post extends on the idea that programming is not about writing code; rather, programming is about solving problems; the code is merely a description of the solution. Without a programmer who understands the code – who has essential context, a model of how the code is meant to function – the code is meaningless.

Going back to our etymological definition, programming means ‘the act of writing publicly’. The goal of programming is not to write code, it is to convey a solution to others as efficiently as possible. A piece of code is a formalized solution, akin to a mathematical proof. But just like academia, you need to provide a lot of context to make sure your proof can be well understood.

Code documents solutions. Transcripts document mental models. You can look at a transcript between an engineer and a coding agent and understand the why behind every bit of code.

So how do I give my agents institutional memory?

I set up a team wide transcript server. All transcripts get sent to this server. So do all git commits, linear issues, slack messages, etc. All my coding agents are required to query this server for research using elastic search and vector search query semantics.

I have a docs.md file colocated with every folder in my codebase. Every time an agent wants to make a change to code in a folder, it has to first read the docs.md file. Any time it wants to push a PR, it has to update the docs.md file for every folder with changed code. Claude Code can generate extremely high quality docs at the end of a conversation, because that is the exact moment when the why of a given change is fully available.

Closing thoughts

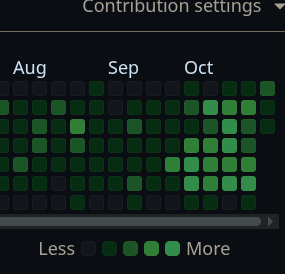

I have been very happy with my setup. Like, the before/after on my github profile is pretty obvious:

I am increasingly of the opinion that coding agents are poorly named. They are less ‘agents that write code’ and more ‘agents that are able to autonomously operate computers’. That is an extremely powerful abstraction.

So far I am excited about four related questions in the space, all of which I am building in:

How can we get as much juice out of these agents as possible? How do we avoid slop, how do we make them good?

What valuable information can we extract from eng ←→ agent transcripts? How can we operationalize that?

Can we build coding agents for non-swe roles? What does a non-swe profile look like?

How can we build better evaluator functions that are agentic themselves? Can we create test suites that are literally just markdown files, with agents that run in containers?

If any of these sound fascinating to you too, drop me a line. And if you’re a software engineer or engineering leader who is tired of feeling fomo about coding agents, give nori-ai a shot and get in touch at https://tilework.tech/.

Great writeup!! I love the idea of the vector database with everything, including transcripts. Seems like an awesome foundation to improve prompting down the line.

Dex from Humanlayer recently gave a presentation where he argues against using folder-level documentation, as it gets out of date. The solution? Using subagents during the research phase to actually read the code itself, summarizing it into the research report. More like on-demand documentation. I will defer the details to his presentation, as he articulates it better than me. Would love to know your thoughts: https://youtu.be/rmvDxxNubIg?si=sE1Bn9DtO6JNbIvf&t=793

This resonates deeply with my own experience building AI-powered workflows. The "distributed network" mental model is spot on - once you stop thinking of Claude Code as a single assistant and start treating it as a team you're orchestrating, everything changes. I've found that the bottleneck quickly shifts from "can the AI do this" to "can I context-switch fast enough to keep multiple threads productive."

Your point about institutional memory is what I've been obsessing over lately. The transcript database approach is clever - I went a different direction and built persistent memory systems directly into my agent setup, where it updates its own context files after every interaction. The difference is night and day compared to starting fresh each session. It actually remembers that I prefer bullet points over paragraphs, that I hate verbose explanations, and crucially - what it tried yesterday that didn't work.

The TDD insight is underrated. I've noticed the same pattern - giving Claude Code clear success criteria (whether tests, type checks, or even just "deploy this and show me the URL works") dramatically reduces the back-and-forth. It's the difference between "help me build X" and "build X, here's how we'll know it's done."

I've been documenting my own setup where I built a persistent AI agent called Wiz that runs scheduled automations, maintains its own memory across sessions, and routes tasks to specialized sub-agents. Similar philosophy to what you're describing, just taken further into autonomous territory. Wrote about it here if you're curious about the architecture: https://thoughts.jock.pl/p/wiz-personal-ai-agent-claude-code-2026